Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

Arrowleaf Balsamroot

Share this! |

|

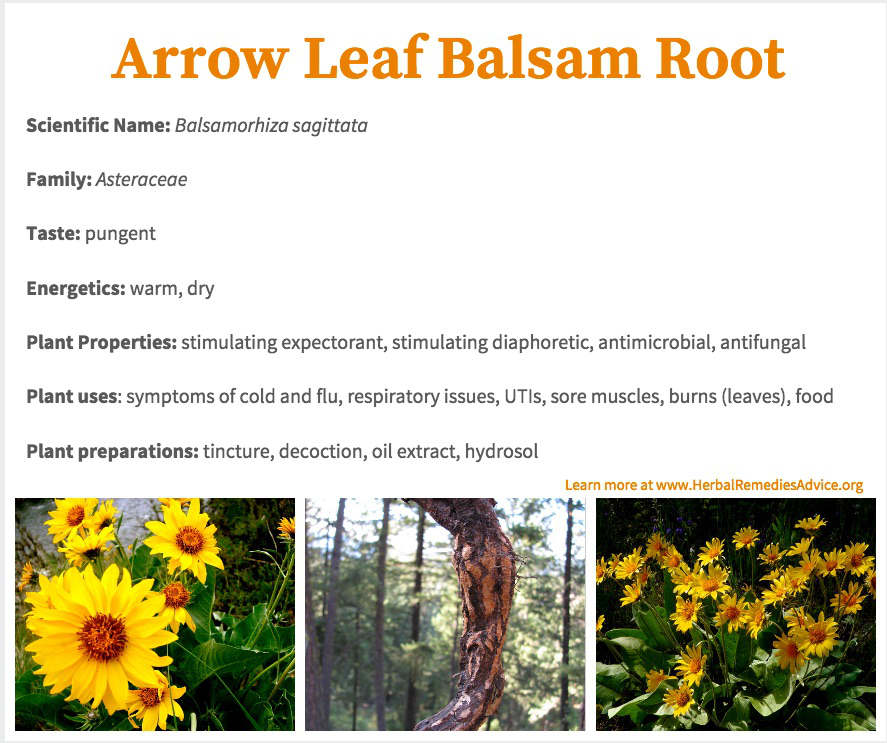

Arrowleaf balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata) is a stunning flower, a nutritious food, and a potent herbal medicine that grows all over western North America. Here’s just a smattering of arrowleaf balsamroot’s medicinal gifts to tempt you…

Arrowleaf balsamroot:

► Relieves the misery of sinus or lung congestion from a cold or flu

► Soothes cold, sore muscles

► Disinfects wounds

► and more…

Between its cheerful blooms, its hillside-stabilizing and medicinal roots, and its pleasantly resinous-tasting spring shoots, who wouldn’t fall in love?

That said, when you harvest roots for medicine, you’re injuring or perhaps even killing the plant. And arrowleaf balsamroot plants take a long time to reach their full stature.

That’s why with this episode you’ll also receive FREE access to a downloadable wildcrafting checklist, so you’ll have the know-how to harvest sustainably, ensuring a plentiful yield for years to come.

After listening in, you’ll know:

► The easiest way to prepare balsamroot seeds for food

► How to work with arrowleaf balsamroot tincture for a sore throat

► The best digging tool for harvesting roots (surprisingly low-tech!)

► What herbs to work with if arrowleaf balsamroot isn’t a locally abundant plant for you

-- TIMESTAMPS --

- 00:00 - Introduction to Arrowleaf balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata)

- 03:19 - Arrowleaf balsamroot in the Spring

- 05:49 - Arrowleaf balsamroot in the Summer

- 08:51 - Arrowleaf balsamroot in the Autumn

- 13:10 - How to ethically and sustainably harvest arrowleaf balsamroot

- 13:47 - Arrowleaf balsamroot in the Winter

- 15:11 - Arrowleaf balsamroot tidbit

Download Your Wildcrafting Checklist!

Transcript of the Arrowleaf Balsamroot Video

|

Arrowleaf balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata) is a stunning flower, a nutritious food, and potent herbal medicine that grows all over western North America. In this episode I’m going to share the many ways that we harvest and work with arrowleaf balsamroot through the seasons. |

My husband and I live in the Methow Valley in the northeastern cascades of Washington State. The valley is just over 50 miles long and is located a couple hours (as the crow flies) from the Canadian border and 4 hours from the Pacific Ocean. The Methow Valley is the original home of the Methow people.

The valley has large tracts of wilderness and a variety of ecological niches, from the sagebrush steppe to riparian rivers, to evergreen forests to alpine peaks.

Each season in the Methow is distinct with intense variations in temperature and plant life. In May, the otherwise drab hillsides of the sagebrush steppe burst alive with a diversity of wildflowers, the most prominent being the beloved, Arrowleaf Balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata).

This wild flower of the Aster family covers hillsides from April to June, often peaking in the middle of May. Besides being a visual delight, this plant has played an important role in the ecology of the Methow for thousands of years.

Dense roots run deep into the rocky soils, preventing erosion; large leaves provide habitat to many scurrying animals and the leaves, flowers and seeds provide an important food source to mammals as small as field mice, to large mammals, including humans. The resinous roots have been an important medicine for humans for countless eons.

Do you have experience with arrowleaf balsamroot? I’d love to hear about it in the comments at the bottom of this page. Your comments mean a lot to me! I love cultivating a community of kind-hearted plant-loving folks! Plus, it’s always interesting and insightful to hear the experiences of plant lovers out there. Your suggestion may also help others!

Okay, let’s dive into this seasonal view of arrowleaf balsamroot...

Arrowleaf Balsamroot in the Spring

As the snows are receding in the valley, Arrowleaf balsamroot offers its first gifts of the growing season. Locating last year’s foliage, smashed flat by the heavy snow, we can find the beginning sprouts of this year’s growth. These sprouts are edible! They are best eaten when they are about an inch in length. As some of the first fresh food to appear, these sprouts are a welcome sign of the turning of the seasons.

We harvest these sprouts by taking only one or two from each plant we walk by to ensure plenty of new growth for the plant. We’ve eaten them raw or cooked them in stir-fries and soups and we mostly prefer them raw, eating them one by one as we harvest from large stands. The sprouts have a strong resinous taste that’s mildly aromatic and overall pleasant.

As the spring continues on, the sprouts grow into leaves and flower stalks, both of which can be peeled and eaten, again taking precautions not to over harvest from one plant or plant stand.

The leaves are large and arrow shaped, hence the common name. Ethnobotanical reports indicate these large leaves were poulticed and used on burns and wounds.

In late April the hillsides are turning green, the first flowers are beginning to emerge and the anticipation of yellow hillsides fills our community. Talk at the farmer’s market centers around whether this will be a good flower year or not. Tourists ask, what are those wild sunflowers on the hills? Many people flock to their favorite hikes to see the stunning displays.

Where we live the purple lupines bloom at the same time, creating a rich tapestry of purples and yellows. Walking through these fields is not only visually stunning but it also smells so very sweet and floral.

Recently, someone commented to me that this flower grows like a weed, but I was quick to interject. Although it’s common in our valley, arrowleaf balsamroot plants take many many years to mature and are difficult to transplant.

Arrowleaf balsamroot has many offerings as food and medicine but the first gifts they offer are the joy they bring with their bright sunny blooms.

Arrowleaf Balsamroot in the Summer

The last of the flower show is fading by mid June, but those wilted blooms bring the next gifts of this sunflower plant, seeds!

The seeds are the size of a grain of rice and are darkly colored ranging from green to brown to black depending on the maturity.

We’ve experimented harvesting the seeds in a couple different ways over the past years. There is a small window of time to optimally harvest the seeds. We like to collect the seed heads when the seeds are visually mature but the head is still somewhat tight. Mature seeds are black instead of a dark green color. If we wait too long to harvest the seeds then many have already been eaten or have fallen to the ground.

We harvest the whole seed head and then lay them out on a sheet in the sun. As the seed head dries, the mature seeds will fall from the seed head and onto the sheet. The seed heads can be further shaken to loosen a few stubborn seeds, but don’t overdo it.

One year my husband did his best to get every single seed from the seed head. He diligently split open the seed heads in his quest for thoroughness. He figured out this is not the way to go about it. Besides getting a few stubborn mature seeds, this method will also remove any seeds that are not mature and worse, will also loosen irritating hairs that will then have to be painstakingly removed from the seeds.

It’s far better to only take what easily falls from the seed heads and leave the rest to go back to the earth. We find that in a couple of hours one person can gather about a quart of seeds. I do not know the exact nutritional value of the seeds but I assume that, like most seeds, they are high in proteins and oils, making them a good source of food.

The seeds are quite small. Shelling these is not an energy efficient way to spend your time and the shell is hard enough to be annoying to eat. We’ve tried milling the whole seeds by grinding them with a mortar and pestle but the seeds go rancid amazingly fast. Roasting them does not soften the shell quite enough to make them pleasant to eat.

The best way we’ve found to eat them is by putting them in our stew pot and simmering them for several hours.

Seed heads are an important food source for birds, rodents and deer so we consciously harvest these from a large area and leave plenty for other hungry beings.

By mid-August the arrowleaf balsamroot is a brown shell of its yellow spring beauty. The once green leaves are brown and crinkled and only a few dried out seed heads stand where hundreds of yellow flowers shone just months before. But, as herbalists, we know the plant is still pulsating and alive beneath the soil surface.

Arrowleaf Balsamroot in the Autumn

|

The roots of arrowleaf balsamroot are the main parts used in herbal medicine. The roots are high in resins with an aromatic and pungent taste. When I nibble on the root I feel the warming and drying qualities as the energy goes to my lungs, creating the need to clear my throat or cough. Oftentimes taking a few drops of the tincture creates a reflex of taking a large breath. Several years ago I was teaching a class to a group of students, many of whom had a cold. Passing around the tincture of arrowleaf balsamroot, students with congestion in their lungs reported feeling expectoration from their lungs and students with head colds felt stuck mucus in their sinuses start to release. |

In this book Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West, herbalist Michael Moore describes arrowleaf balsamroot as a cross between echinacea and osha, in that it’s both an immunomodulator and a pungent herb that affects the respiratory system.

I prefer to use arrowleaf balsamroot as a fresh root tincture in 95% alcohol. Or to steep the mashed roots into honey.

Arrowleaf balsamroot is a stimulating expectorant, making it great for congestion in the respiratory system. A stimulating diaphoretic for supporting the fever process when you feel cold, and an antimicrobial which is great for sore throats.

For sore throats I like to mix 10 - 20 drops of the tincture with a spoonful of honey that is then swallowed. I often combine it with a tincture of cottonwood buds.

I have yet to use arrowleaf balsamroot for a UTI, but Michael Moore describes arrowleaf balsamroot as a disinfecting diuretic. Darcy Williamson reports that taken in too large of a dose it will create kidney irritation.

For external use it infuses into oil very nicely; because of the resins I use heat to extract the root. This warming aromatic oil relieves pain brought on by blood stagnation such as sore shoulder muscles or tension associated with coldness. Used as a liniment it also lends itself well to sore muscles and can also be used to disinfect wounds or kill fungi living on the skin.

Although lacking experience with this myself I’ve seen ethnobotanical records indicating that arrowleaf balsamroot is useful for gastrointestinal complaints and toothaches. With its pungent and antimicrobial properties, this makes a lot of sense.

You might be wondering how to harvest these medicinal roots.

Arrowleaf balsamroots can have incredibly large roots! These roots often take decades to grow! But I don’t recommend trying to harvest these! Not only are large roots hard to dig up, often taking hours, they are also really hard to process.

Instead, look for smaller plants with a modest amount of foliage. You also want to find plants that are growing on flat ground. Those plants on steep hillsides are doing an important job of keeping the hillside in place. And, of course, you want to harvest from a healthy stand with lots of plants.

|

I use a traditional digging tool for my root harvests. I find sticks

are often easier to use as a harvest tool than shovels since shovels can

easily slice roots and can often get caught on the plethora of rocks

hiding in the soil where arrowleaf balsamroot lives. I like to harvest taproots about the size of a large carrot. A hard outer bark envelopes a woody root in the center. I break apart the outer bark with a hammer, mince the inner bark and tincture them both. The resins from the root will cover your cutting board, knife and hands. Alcohol works well to clean them off. |

If you live in an area where arrowleaf balsamroot is abundant, then

it’s worth learning how to ethically and sustainably harvest this plant

as food and medicine.

Our book, Wild Remedies: How to Forage

Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine, shows you how to

harvest many different medicinal plants.

If arrowleaf balsamroot isn’t a locally abundant plant for you then I recommend using garden herbs like thyme, sage, and even elecampane as a substitute for congested respiratory conditions.

Arrowleaf Balsamroot in the Winter

In the North, winter is a time for animals and plants to rest. In our valley the ground is covered with many feet of snow blanketing all the plants beneath the soil. Arrowleaf balsamroot rests in its roots, waiting until spring to bring forth its many gifts once more.

Above ground we nestle next to the wood stove and give our thanks for the medicine of arrowleaf balsamroot.

If you want to learn how to make potent herbal medicines from the plants that grow around you, then check out our course, Rooted Medicine Circle, which enrolls every January. In this ten-month course we guide you, step by step, in making your own powerful herbal medicines in your own kitchen. Visit RootedMedicineCircle.com to get all the details and sign up for the waiting list.

One of the best ways to retain and fully understand something you’ve just learned is to share it in your own words. With that in mind I invite you to share your takeaways with me and the entire Herbs with Rosalee community. You can leave comments at the bottom of this page, or simply hit reply to my Wednesday email. I read every comment that comes in and I’m excited to hear your takeaways, thoughts and experiences with this precious native plant.

Okay, you’ve lasted to the very end of the show which means you get a gold star and this herbal tidbit…

As mentioned, I live in the Methow Valley, which is the original home of the Methow people. The arrowleaf balsamroot covers the valley here and is an important plant to the Methow people. It’s possible that the name Methow, may come from the Salish name of arrowleaf balsamroot. My friend David LaFever is sharing a bit about this here. Here's also link to a video from Michael Pilarski, a regional herbalist, showing how he processes these hard roots.

Lastly, I’ll leave you with this quote from Scott Kloos from his book, Pacific Northwest Medicinal Plants, “Think of it this way: the flower heads receive the golden nectar of the sun and send it to the roots, where it is concentrated as a resin. In this same way, balsamroot brings joy and light to the dark places of our beings. Follow the direction of the upward-pointing, arrow-shaped leaves, and allow yourself to be uplifted."

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.