Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) with Rebecca Beyer

Share this! |

|

What happens when we follow one plant deeply enough to uncover its stories, traditions, and medicines?

In this episode, I sit down with herbalist, artist, and folk magic researcher Rebecca Beyer to talk about her lifelong devotion to spicebush (Lindera benzoin)—a plant rooted in Appalachian folk tradition and brimming with story.

Rebecca shares how a difficult illness first led her to herbal medicine, and how she eventually came to see spicebush as her patron plant. We explore its many gifts—from its role in spring tonics and colonial kitchens to its modern uses as a warming, aromatic ally. Rebecca also invites us into her creative world, where her herbal practice meets her art, tattooing, and deep love for regional traditions.

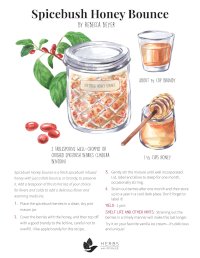

Fresh spicebush berries are notoriously difficult to dry, so Rebecca likes to find other creative ways to preserve their peppery, citrus-spiced flavor. She’s shared her recipe for Spicebush Honey Bounce—spicebush berries infused in honey, plus a little something extra! You can find a beautifully-illustrated copy of Rebecca’s recipe in the section below.

By the end of this episode, you’ll know:

► Why spicebush holds such a beloved place in Appalachian folk traditions, bridging the worlds of food, medicine, and seasonal ritual

► Four medicinal benefits of spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

► Rebecca’s trick for drying the fruit so they keep their flavor for years and don’t mold—quite a challenge for these juicy berries!

► Six ways to work with spicebush for food and medicine, from the bark to twigs, leaves to fruit

► Why embracing many teachers—and a community of learning—is key to becoming a better herbalist

► and so much more…

For those of you who don’t know her, Rebecca Beyer is an Appalachian folk herbalist and magical practitioner, tattooer, author, and crafts woman. She studies and teaches foraging, regional folk medicine and handicrafts at her home in the mountains of Western North Carolina through her school, Blood and Spicebush School of Old Craft, and tattoos at her studio, Pars Fortuna.

This conversation is full of history, heart, and plant wisdom. Whether you’re new to spicebush or already love the plants of Appalachia, I know you’ll come away inspired by Rebecca’s joyful relationship with this fragrant, generous shrub.

Click here to access the audio-only page.

-- TIMESTAMPS -- for Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- 00:09 - Introduction to Rebecca Beyer

- 01:59 - Rebecca’s plant path

- 08:19 - How Rebecca came to know spicebush

- 11:28 - Medicinal benefits of spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- 17:57 - Spicebush Honey Bounce recipe

- 20:57 - Spicebush in food and tradition

- 25:27 - Rebecca’s new book, The Complete Folk Herbal

- 35:27 - Rebecca’s current herbal projects

- 38:49 - What Rebecca wishes she’d known when she first started out with herbs

- 42:00 - Student spotlight

- 43:09 - Herbal tidbit

Get Your Free Recipe!

i

Connect with Rebecca

- Website | BloodAndSpicebush.com

- Instagram | @bloodandspicebush

- Facebook | Blood and Spicebush

Transcript of the 'Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)' Video

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Welcome to the Herbs with Rosalee Podcast, a show exploring how herbs heal as medicine, as food, and through nature connection.

In this episode, I’m joined by Rebecca Beyer, herbalist, tattoo artist, folk magic researcher, and all-around plant storyteller. Rebecca has a special devotion to spicebush (Lindera benzoin), a plant woven deeply into Appalachian folk traditions. She shares how this unassuming understory shrub became her patron plant from its role in spring tonics, to its peppery red berries that once stood in for allspice. We also talk about her brand new book, which is gorgeous, The Complete Folk Herbal. This brings together history, art and everyday herbal wisdom in such a beautiful way. This conversation is rich with tradition, creativity, and plant love.

I can’t wait for you to join us, and if you enjoy this episode, please give it a thumbs up so more plant lovers can find us, and be sure to stay tuned to the very end for your herbal tidbit.

Tired of herbal overwhelm?

I got you!

I’ll send you clear, trusted tips and recipes—right to your inbox each week.

I look forward to welcoming you to our herbal community! Know that your information is safely hidden behind a patch of stinging nettle. I never sell your information and you can easily unsubscribe at any time.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Rebecca, this has been a long time coming. Welcome to the show!

Rebecca Beyer:

Thank you so much for having me.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, my gosh. So, first things first, I just want to crawl into the screen and go into this world that you live in. This is like—I feel like every fantasy herbalist dream I’ve ever had. I just—it looks like the coziest of all coziest books, and just—yeah, so that’s what I–I hope that’s not a creepy thing to start out with. It’s so lovely. And if you’re listening to the podcast, I’m sorry because it’s just like you have to go check this out. I mean, it’s like—I mean, this has to be every herbalist’s dream. I’m just going to project that onto you.

Rebecca Beyer:

You’re so sweet. That’s actually my tattoo shop and my writing studio.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I would get a tattoo there for sure.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, yay!

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Lovely. Well, welcome to the show. Thanks for bringing all the cozy vibes with you.

Rebecca Beyer:

You’re so welcome. Thanks for having me again. It’s a dream to get to talk to you.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, lovely. Well, yeah, it has been a long time coming. You’ve been highly recommended on numerous levels, and really excited to talk to you, to get to know you a bit, to talk about your chosen plant, to talk about your upcoming book, all the things I’m excited for, but let’s begin with Rebecca’s plant path and what brought you here to us today.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah. It’s—it’s so funny. I—when I wrote my first book in 2021, my publisher was like, “You need to write an intro about yourself.” I hadn’t really thought about my—my story, you know, but it was actually a nice opportunity to be like, “How did I get into this?” I was not raised around plants. I was raised on farms here and there throughout my childhood, moving a lot in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and California, which are the three different places I lived as a child, but I was not raised with a strong connection to plants. I was with animals. But when I was 19, I got really sick. I think a lot of us became herbalists because we got sick, right?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah.

Rebecca Beyer:

And I had severe mononucleosis for over a year with no relief, and had severe brain fog, and exhaustion. I would narcoleptically almost fall asleep while sitting up, and very scary symptoms that were extremely upsetting. I went to six different doctors. I was given no relief. I think this is a story many people can relate to. And then I met an herbalist in Burlington, Vermont because I went to the University of Vermont, and I have a degree in plant science, Plant and Soil Science. I met Laura Brown of Purple Shutter Herbs, who has, unfortunately, passed on. She passed away from cancer. She said, “You know what you need? You need goldenseal, thyme, and boneset, and then you’ll get fixed up.” She was really stern with me and I was like, “Okay. I don’t know what any of these things mean. I’ll give it a go.” So, I followed her instructions and made this decoction, and within three days—I had had a chronic cough for over six months—a dry, hacking cough, and my symptoms resolved almost in a week. I was so incredibly shocked because I went in expecting it not to work. I didn’t have any—I didn’t know anyone who was an herbalist, except for this person I had just met, and I ended up just radically changing my whole life based around this. At the time, I was a medieval history major. I was interested in plants, but more from a historical perspective than the actual doing-stuff-with-them perspective.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Like what plants they grew at the abbey or something like that.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah. I was more interested in the folk side of things and the history and ethnobotany, which I can’t say is not still the case. All that to say I switched my majors in college. I ended up shifting a lot of what I was putting my energy towards, and just from there, I ended up moving to North Carolina after I graduated, and I moved here in 2010. I apprenticed with Natalie Bogwalker of Wild Abundance and learned more primitive skills and foraging plants, and then I met Juliet Blankespoor and started—I didn’t go to her school, but I would cook for her school and she would let me sit in on the classes. It was really amazing. From there, of course, had so many teachers, and I actually did not go to herb school, which is weird, but I am—yeah, I’ve gone to a lot of conferences and talks and read hundreds and hundreds of books, and—I think my plant path has really been largely two ways. It’s been academic, and then it’s been very folksy and historical because I had my interest in living history and I’m working in the 1800s as an interpreter of farms.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, wow.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah, so I think those two things kind of came together, my science background and my interest in history has kind of crafted me to be a regional, historical interested herbalist, which is where I now really identify as an Appalachian folk medicine researcher, writer, and practitioner, and a forager, and a primitive skills teacher, and earth skills teacher. I’m sorry it’s so long-winded.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

No, that’s lovely. It’s absolutely lovely. I can’t get over the thought of drinking a goldenseal, boneset, thyme decoction, like-

Rebecca Beyer:

It was disgusting, but I did it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s intense! I had a similar situation that I was also very sick. I was also not given choices in Western medicine, and I went to a TCM practitioner and did TCM decoctions, and so—I remember I did it by the sink, and so, I had the TCM decoction, and then I would have apple juice, and I would do it by the sink because sometimes it just—I couldn’t keep it down. I mean, it was just so bad. I think I probably would be better at it now. It was like, like you, I was not an herbalist. I was not—this was all new to me. Those were some interesting tastes, but I think—I have no doubt that the goldenseal, boneset, thyme—because even thyme, although that’s lovely, it’s a very strong taste, and then the boneset, and the golden—I mean, yeah, yeah. Kudos to you for doing that, and then what an incredible healing turnaround just to have it fixed just like that.

Rebecca Beyer:

And from what I know now with practice under my own belt, I don’t know if that’s the formula I would have given me, but I have to say I had a lot of other issues that were co-occurring that I won’t go into that were—I will say greatly helped by those things. She ended up being a person I would go to again and again, her beautiful, beautiful shop in Burlington. I’m so grateful to her.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It sounds like a—that doesn’t sound like a formula I would necessarily come up with, but when you said it, I kind of—I just had the sense of—like that was an intuitive formula that just came together and obviously, was very powerful.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah. Talk about bitter, right?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, yeah. Well, thank you for sharing your story with us, and it’s interesting to hear how these different interests of yours have converged, and I’d love to hear about spicebush. I’m guessing this is a very important plant to you.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah. In 2014, I was like—you know, I had been just really devoting myself to studying plants and crafts. I also sing Appalachian ballads. While I was born in Appalachia in Western Pennsylvania, I was not raised in cultural Appalachia, but because I live here now—as a young person, I was like I just want to learn everything I can about my region. I actually met spicebush the first time in Upstate New York while I was doing an archaeological dig for a college class on archeology. I think I was 18 and I—my teacher pointed out spicebush. She said, “You know, you can chew on this plant.” I was like, “You can chew on plants? What? You’re just going to chew on a stick? That’s wild!” He did it. It had berries on it. It was in the fall in Hudson, New York, right outside of Poughkeepsie, and I was just really shocked that you could do that. It really lit me up to see this direct interaction with this plant. So, I had made note of it, and then when I moved to Appalachia, it was everywhere. It was much more common and I ended up purchasing a property in 2012 that was covered in it. We actually named our community “Lindera,” which was when I first met jim online, I guess years ago. I was like, “jim, we both love”—jim mcdonald that is I’m speaking about. We both love Lindera and I think it’s one of the reasons we were able to connect when I first met him two years ago.

But spicebush, yeah, I don’t know what it was. When I first started blogging about Appalachian folk medicine and magic and the historical uses of plants in our region, I named my blog, Blood and Spicebush. Through that, I feel like I chose my patron saint of plants and have forever been associated with it joyfully. One of the things I love most about Appalachian folk medicine is its rituals, not in the way I think a modern use of that word, but in the spring tonics and doing things at a special time. Aside from the right plant for the ailment, it also has to be the right time, right? Much like in medical astrology in Ayurvedic medicine and things like that, and knowing that the spicebush was cleaning the blood in these spring tonic traditions really attracted me not only to its, you know, the fact that it has been studied for its antifungal compounds, but also, its historical uses as the springtime aligned cleansing alterative.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It’s lovely. It just speaks a lot to just that—like you’re speaking of the getting-to-know-your-region and how it’s not just the plants that are there, but it’s how we live through the seasons with the plants as well.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I actually know very little about spicebush. I was telling you beforehand, the only—the first time it ever came on my radar is because jim has his Lindera program, and I was like, “What’s Lindera?” And I had to look it up. I didn’t ask him because I wanted to appear knowledgeable. The first time I met spicebush was a year ago when I went to visit jim, and he showed me spicebush on his property. So, this is—we have now the sum total of my spicebush knowledge, so I’m excited to hear more and just different ways you like working with this plant.

Rebecca Beyer:

If you want, I can share just some brief information about it to help you get to know them a little bit better.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Sure! I’m here for it.

Rebecca Beyer:

That would be helpful. Okay. Great! I don’t want to wear you out with too many details, but, you know-

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I love all the details.

Rebecca Beyer:

Me too. I’m like, “More please.” It’s Lindera benzoin in the Lauraceae family. Whenever I think about Appalachia too, I always think of sassafras. Spicebush and sassafras are besties. It’s an easy way to remember them. They’re both aromatic, warming at spring tonic barks, and they go together historically in the same mixtures of decoctions. It would be given in the springtime. We mentioned earlier the range of spicebush, and like—I may—forgive me if I’m not mentioning every place that it grows, but it would be from Southern Canada to Florida, and over towards Kansas, and down to the parts of Texas you can find it, but it is not—it makes sense you don’t work with it because it doesn’t grow where you live, which you’ll have to tell me, I’m not exactly sure where we’re calling in from today, but I think in California, yeah?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Washington.

Rebecca Beyer:

Washington, excuse me. I love Washington, but that’s roughly its range, definitely like one of the disjunct plant populations that Asia also shares with us in Appalachia. They have one Lindera japonica in Eastern Asia, and we have Lindera benzoin. They have black berries and ours have red berries, which I think is so cool.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It’s interesting, yeah.

Rebecca Beyer:

It’s used in Chinese medicine as a warming diaphoretic in the same way and in Japanese Kampo medicine where it also grows. I believe for a similar energetic kind of signature, which I just think is incredible, and I love seeing that across the continent—continent’s connections. We use the root—excuse me—we use the bark, the leaf, and the berries for decoctions, for fevers—that is its claim to fame historically, and that, of course, comes from indigenous use. We now know from current research—there was a study done in 1992 and then another—I think it was 2008—about the volatile oils, and they’re very effective against candida topically, which is pretty lovely, and against—I think it’s called T. rubrum, the fungus that causes athlete’s foot. So, I have—in my current uses of the plant, I often will use it as a vaginal wash or soak for yeast infections, for jock itch, and things like that. And then, I love the berries. That’s my favorite, favorite part. They’re bright red, like fire engine red, almost like a shiny, smooth, waxy-looking, little oblong cherry. They’re about the size of a raisin, which they look like a raisin when you dry them. The berries taste a lot like orange peel and black pepper, with a hint of fruitiness, general fruitiness. They were used as an allspice replacement in colonial America because spices were so expensive.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, it’s fascinating. I don’t know, and again, maybe because the spicebush hasn’t been on my radar, but I don’t know that I’ve ever seen spicebush being sold, like the berries or the bark or anything.

Rebecca Beyer:

No, it’s really fallen out of popular use. It didn’t really make it into the dispensaries and the Eclectic books that a lot of us are familiar with until the 1830s because of racism. It was one of the herbs that was considered not extremely potent medicinally by white doctors at that era, and so, it wasn’t really included until they were getting the oils out of it for topical applications for rheumatism, which is I feel like where it was pulled into the dispensary and things like that, the King’s dispensary. You don’t see it mentioned a lot in the literature. It is very, very important in indigenous medicine, and it was used widely by Appalachians and people from the Ozarks. Like you mentioned earlier, you had heard in Arkansas it also grows. It’s a very important plant spiritually and medicinally there. I would say its uses in Appalachia are directly from indigenous use, and I feel like energetically too those red berries always remind me of the kind of like bright red top of the thermometer when someone has a fever. Feverbush is its other folk name, as well as “Benjamin bush.” I have even heard people call it “snapbush,” and if you break the twigs, they do just snap right off, so it’s pretty interesting.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Is this a fairly common plant in the areas where it does grow?

Rebecca Beyer:

It’s definitely common here. It literally is the most common understory shrub on the property that I live on. I can find it in any edge of a forest that’s moderately undisturbed, especially if there’s some moisture. It does well with pine, so you’ll find it around a lot.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s so lovely! I love the bioregional herbs that are also, you know, ubiquitous, and just the ability to work with them as a bioregional herbalist, the opportunity is there and the connection with the plant is there, and like you said, being able to work with the plant through the seasons as well.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, yeah. I really—and the nice thing about spicebush—I always tell my students this—is you don’t have to preserve it unless you want to preserve the berries, because all year round, the bark is always fragrant. It is always wonderful. You can use the leaf, but I find them to be pretty bitter, so I generally make tea from the twig, which is just very sweet and warming and spicy. It’s so pleasant-tasting. It tastes—you could just drink it for fun, like it’s just delicious.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, that sounds like fun. I want to try that.

Rebecca Beyer:

I’ve made just like drink syrups from the twigs even and mix them with seltzer water. They’re just so delicious.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Ooh, that sounds lovely. You’ve also shared a recipe with us using the berries. I’d love to hear more about that.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, yeah, definitely. I am going to read it off my little paper here, so I don’t—I tend to be one of those people. Tell me if you relate with this, where recipes are hard because you’re like, “Just throw a little of this and little of that,” so I did write it down for myself too. I call this “spicebush honey bounce,” because it is—I make it with the raw berries, but you can make it with the dried berries too. This is an infused honey that I use to add to, you know, warming diaphoretic teas like elderflower. Mint and yarrow tea would be nice with this mixed in if you have a fever. That’s where I use it most often. You can also put it on any type of yellow cake and it will make you very happy.

So, essentially, what I do is it’s a fresh spicebush infused honey with a little bit of brandy that helps preserve it because of the fresh berries being added. If you don’t want to use alcohol, just exclude the brandy from this recipe. This makes about a pint, and all you really need to make this recipe is a pint jar, a clean spoon, and two tablespoons of well-chopped or crushed fresh spicebush berries. Just use one tablespoon of dried. I actually have a coffee grinder I’d use just for spicebush berries.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Really? Not just for herbs, but just for spicebush berries? Ooh.

Rebecca Beyer:

Because I think—I didn’t mean to become a one-trick pony with herbs, but I named my whole business, Blood and Spicebush, so I have to show up with the spicebush berries at the function. You know what I mean? They’re very hard to dry. One of the tips I will give you before jumping into this recipe if you’ve never worked with these before, I was told—and I think this is something that’s kind of common from books and people—that they’re impossible to dry and that they will always mold. I was like, “Really? Is that really true?” What I end up doing is I have an Excalibur dehydrator and I dry them on the fruit setting for four days, and they don’t mold. They will last for years. So, that’s my trick. My trick is to use a lot of electricity, unfortunately, and really, really dry them out. When you take these, you’re just going to put a cup and a half of honey over those crushed berries, and then I use just enough brandy to take it to the lid line. You can gently stir that or you can just let it sit for a little while, and just like an infused honey, you can let it sit for about four weeks. I actually just leave the spicebush berries in there indefinitely because I like to scoop them out to use them in recipes anywhere I would use cinnamon, orange peel, black pepper, allspice or chai-like flavors.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That sounds absolutely lovely! I imagine you just have this going on all the time.

Rebecca Beyer:

I have a lot of it in my house and I also keep a lot of dried spicebush berries. Traditionally, it’s used as a seasoning for meat. One of my teachers, Doug Elliott—I don’t know if you’re familiar with him.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I am, yeah.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, good. He’s such an angel.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

He is.

Rebecca Beyer:

He told me that they would take—if you had—if you’re cooking game meat like a possum or a raccoon, you stick enough spicebush twigs into them to make them look like a porcupine, and then roast them. That was the way to flavor than meat, so I use it in broth and in red meat broths, and it’s delicious.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It sounds incredible. Now, I wonder though because my brain is just going off on this other tangent—do you and Doug get together and sing together, like-

Rebecca Beyer:

We do.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah? That would be a good show.

Rebecca Beyer:

I’ve known him since 2011, and I have sang—one time, I remember me and him and his son, Todd, went toe-to-toe on how many verses of Cluck Old Hen we knew collectively, and I think we sang 15.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Wow! That’s fun.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah, it was wild, and The Crawdad Song, “You get a line, I get a pole.” We’ve done that one too.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Fun, fun. For folks who are interested in trying the “bounce,” we do have a beautifully illustrated recipe card for you. You can download that at herbswithrosaleepodcast.com or just check out the show notes. They’ll be there for you. Thank you so much for sharing that recipe with us.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, it’s my pleasure. I love making it and it’s really an easy way if you don’t want to dry the berries too to preserve them.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I’m really interested about the other ways you mentioned as a spice for food. If other folks have been using it like that, please let us know in the comments. It would be fun to hear about that. You mentioned specifically for raccoon, which just randomly reminded me I was a vegetarian for many years, and then I started down the primitive skills, earth skills path, and the first meat that I ate was raccoon.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, my gosh. I was the same way. I was a vegetarian for six years until I started working in Living History, and then got into the Earth Skills community. Mine was a chicken that I killed myself was my first-

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, wow.

Rebecca Beyer:

Meat after six years of vegetarianism, so I love that you—we’ve had that similar experience. I’ve eaten a lot of raccoons, I’ll say.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, yeah. I remember the ribs were kind of dry, but it would be interesting to try with spicebush, for sure.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, definitely. Braising it in spicebush too. We once stuffed it with oranges and then dusted them with spicebush berry dried, and braise it in the juices. It was—it was like orange raccoon, it was delicious.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Wow. I have to say I’m very intrigued now about spicebush. I feel like I need to just head over to Appalachia, hang out for a while, work with it in all the ways. Was there anything else you’d like to share about spicebush before we move on?

Rebecca Beyer:

Let me think. I think the main things that I always think about spicebush are just its—yeah, its history as part of the spring tonic tradition, which was directly brought into the uses of all the different peoples living in Appalachia by Indigenous practitioners. And it has special butterflies associated with it, like the spicebush swallowtail. It’s an ecologically very important shrub as well, which I’m not—I’m kind of a pain in the butt in that I’m very ethnobotany-centered, and don’t always take the time to learn more about my butterfly buds, so I appreciate all the people that have messaged me about different ecological roles it plays. I’m excited to learn more about that myself too.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Lovely. Well, I am really excited about your newest book, Rebecca. I feel very honored that I got an advance copy. It’s just so beautiful! When I took it out of the packaging it came in—I mean, there’s something about a hardback book in itself that’s just so lovely, but just, I mean, the—the feel of it is just so incredible, and I was just really loving the illustrations and the whole look and feel of it, and then it had just escaped my awareness. You did all the illustrations too. I mean, what a book!

Rebecca Beyer:

It’s—I’ve been working on it for two years and I wrote part of it while undergoing—I lost my entire tattoo shop, my entire herbal library, and my writing studio to Helene. It was a total loss. It was completely destroyed—13 feet of floodwaters, and I was finishing my book during that time and it was a lot to stay on my deadlines while dealing with total destruction and watching my region just go through one of the hardest things we’ve been through in the past 20 years. So, I feel very proud of it, and I’m also, of course, at this point, like, “Oh, I wish I could go and edit it again.” No. It’s hard to be truly satisfied with something you create, and I’m also just honored that anyone wants to read anything that I write.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, it’s absolutely beautiful. It’s called, The Complete Folk Herbal, and there are, I want to say, that a hundred herbs in here? Is that right?

Rebecca Beyer:

I think there’s 92, which is kind of a random number. Almost a hundred herbs.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Almost a hundred herbs, and it’s just—I mean, the whole thing is just so beautiful, and I saw so many of my favorites in here from—you know there are things like local, like vervain. You’ve got cleavers in here, ginseng. There are Appalachia ones as well as so many others too. I think I saw cardamom in here. Is that right?

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah, I use cardamom so much. I think I—it’s kind of a selfish book. When they suggested—my publisher wanted me to use the title, Complete Folk Herbal, and I was like, “No. I don’t want to call it that. Nothing’s complete.” We were talking about John Gerard’s complete folk herbal from the 16th century. His is called, The Complete Herbal. But I was like, yeah, for me, it’s like this is the complete list of my Top 92 in my personal life.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

You made it work. You’re like, “This is how it works in my brain.”

Rebecca Beyer:

How do I rationalize this title choice because obviously, nothing is complete? There are thousands of herbs in the world, but it’s the ones I find myself going to, and the ones that I thought most people would have the most use for, and then of course, with a nod to the ones in Appalachia. Kudzu is included in it. I included rare herbs in it, like ginseng, you mentioned. Not to encourage their use, but because I’ve noticed in my teaching and in hearing other teachers, sometimes people are choosing not to let people know. Like I mentioned earlier, I used goldenseal, a very endangered herb, twenty years ago, when I was treating myself for this illness. And in my opinion, if I teach my students how to correctly identify and what the actual indications for a rare herb is, they’ll be less likely to use it willy-nilly or for TikTok reasons for herbs, right? So, in my opinion, I really hope this book can help clear up some—what Paul Bergner calls “herban legends,” which I love, H E R—her-ban legends for the British listeners. I couldn’t help myself. My real hope with this book is that it’s a good reference. I really tried to source it and cite it well, so that it could act as a reference work, and also, just be something beautiful that is helpful. And, yeah, I’m excited. I’m curious to see how it will fit into the plethora of beautiful herbal books that are out there.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It’s going to fit right in. Absolutely stunning! I’m curious. I would love to hear more about the process of illustrating as well. So many beautiful illustrations and they all just—I don’t know. There’s such a consistent vibe through the whole book.

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I’m wondering how you chose that. How did you decide, “Okay, this is what I’m going for?” Was it like first shot? Or did you work with a couple of different styles before you decided on one?

Rebecca Beyer:

That’s such a good question. No one has ever asked me that. I am tattooer. That is actually how I make most of my living. It supports my herbal hobby. I specialize in Medieval Botanical and etching style tattoos. So, I drew the illustrations in the style I have come to be known for as a tattooer and as a nerd for medieval history and old woodblock prints. I did a kind of like—because I’m kind of going off on John Gerard’s, like the complete folk herbal from the 1600s kind of inspiration. I was like, “What can I do to make a modern take on that traditional woodblock style?” and that was what informed a lot of the drawings.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Wow! That’s so cool—the layers there. Yeah, got to love artists and history too. I just love it. It’s so beautiful. How—were you working on the illustrations and writing kind of simultaneously? Did you do one and then the other?

Rebecca Beyer:

I did the writing first, and then I did the illustrations, but we did probably six rounds of intensive editing because my publishers don’t know about herbs. They are publishers, right? That’s their—their knowledge base which I don’t know about. So, my friend, Abby Artemisia, who I used to run a little herb school with called, “Sassafras School,” actually was my fact checker. She went through and did kind of a educated read for me, and then sent it to my publishers, so we were going through all these edits, and I’m doing all the drawings at the same time. I did 60 something illustrations. It was a lot of work. It was a lot. My partner just would bring food to me on a plate and slowly back away while I was doing all these illustrations.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, yeah. I hear you. Did you have any—did you have to hold your ground at all with the publisher and editors in terms of—like you wanted something in and them not knowing herbalism, maybe didn’t think like that should be in there? Was there ever that kind of thing happening where you had to be like, “No. Actually, this is—this is important. We’re keeping this,” or something along those lines?

Rebecca Beyer:

One of the coolest things about working Simon & Schuster—and my book is out of Simon Element, which is like their natural imprint that does more of the health stuff that they put up—is they never tell me what to do with my writing. The only thing that happened, which was nobody’s fault, and I say this with a lot of grace, is they wanted me to write the recipes in it like it was a cookbook. I had to remind them that like, “No, that’s not how,” and somebody actually went through and edited the entire document and messed up all my recipes.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Ooh.

Rebecca Beyer:

As a cookbook. I was like—it took me like days to fix it and I was so frustrated. It was nobody—it was just a misunderstanding, but-

Rosalee de la Forêt:

What do you mean by that “like a cookbook?”

Rebecca Beyer:

They would be like “This serves this many people.” The how much—like the way that they wanted me to do the proportions and things. I was like, honestly, these recipes—like the tincture recipes—I was like, “One to two, 95 proof, fresh,” and they didn’t like that. They were like, “What? What?” I was like, “You have to read the beginning of the book to understand.” So, because they were not reading it and taking it in as like learning the material, a lot of times, my edits they would offer me. I’d say this to anyone writing an herbal book: Hire one of your friends who is an herbalist to check your work for you. My other friend, Juliette Abigail Carr, from Old Ways Herbals, also looked through the work for me and gave me feedback on it. So, having people in your world that know what you’re talking about help you edit is invaluable. Your publishers can’t quite do that. It’s out of their wheelhouse.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, yeah. That’s a really good tip. I remember with my first book, the publishing house that I was with, they had like—their thing was that—I don’t know why, but their standard was that you wouldn’t list water as an ingredient because it’s assumed that everybody has water was the feeling behind that. And so, my first book, Alchemy of Herbs, there—they took out whenever I had water as an ingredient, they took it out. It’s in the directions, but not in the ingredients. I just happened to mention that during—when writing the second book, I was like, “That always bothered me and I just think it’s weird.” They were like, “Oh, we can do it the other way,” so I got water in the second book. I was like, “Man, if only I had known.” I just kind of accepted it. It was my first book and I was just like, “Okay. We’ll just leave the water out.”

Rebecca Beyer:

I totally get it, and I’m glad this is my third book. I also put a book out about Appalachian folk magic called, Mountain Magic, with Quarto Press two years ago. I’m really grateful that I got those two first, and this book is my biggest book. It is also not focused on the magical or mystical because I wanted it to be more comfortable for a wider audience and more useful for just—regardless of what your beliefs are around that, that it will just be an herbal. I’m glad I had the experiences and the mistakes that I made, and knowing you could just ask for what you want, and they’re usually like, “Of course, no problem,” and I just [unclear]

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Really well done on this. It’s absolutely stunning. I’ve been enjoying going through it, picking out my favorite plants, reading about them, so yeah, I’m excited to see it go out into the world this October, and congratulations on that!

Rebecca Beyer:

Thank you so much. It means a lot coming from you.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Do you have any other herbal projects you have going on that you’d like to share with us?

Rebecca Beyer:

Well, I’m always working on writing, and right now, what I’m really feeling called towards—this is just my nerdy stuff—is I’m working on some projects on Pennsylvania Dutch folk uses of plants and continuing to compile information for a helpful work about Appalachian folk medicine that is more practical and less antiquary, if that makes sense? I’m kind of going through some of the classics from history, which I did a little bit in my book, Mountain Magic, but I’d like to do a piece and I’ve started working on it, so that will be something I’m really getting a lot of joy out of working on.

Of course, I teach a course in person every year called Hedgecraft, and it is about—it is my attempt to help my students learn how to identify plants safely and effectively, and also learn their historical, present uses, scientific uses, and how they can use them everyday in their lives in a meaningful way that’s tied to the Wheel of the Year and is accurate historically in terms of naming where things come from, what cultures led us to know them, and just really deep diving. We combine craft like basket-making with things like woodcarving and also making wild foods and spiritual crafts, and things like that.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That sounds absolutely magical. What a cool hands-on way to just be able to explore all these converging interests of the land and being in place.

Rebecca Beyer:

Thanks so much. Yeah, if you want to look at any pictures, I have a page on my website, which is www.bloodandspicebush.com. If you click on Hedgecraft, under Classes, you can see photos of some of those crafts if you’re kind of curious like, “What the heck is that?”

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I’m curious. I’m going to go check that out. Speaking of that, you have your website. What are other ways people can find you?

Rebecca Beyer:

You can also find me on Instagram. It’s just “bloodandspicebush,” no spaces or anything, and I am not as active on Facebook, but I do occasionally post there. But Instagram, as an elder millennial, Instagram is my realm.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Nice. You do a beautiful job there, and the book is going to be available wherever books are sold starting in October. Are you going to sell them yourself or is this like people should go to their local bookstore and put in their order?

Rebecca Beyer:

Yeah, because Simon & Schuster are such big boys, I do not sell my own books because I have to buy them from the publisher and then resell them. I’d rather just send people to your favorite local bookstore because they will probably be there, and if not, if you ask them, they could order them for you.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Tell them to get several copies in because this is [unclear]

Rebecca Beyer:

I’ll be doing some book events in my local area at Malaprop's Bookstore, which is one of our favorite local bookstores, and also, Firestorm Books in October.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Wonderful! Oh, it’s going to be so much fun to see this out to the world. Again, just not only have your beautiful compendium of writing, but these beautiful illustrations as well. People are going to love it.

Rebecca Beyer:

Thank you. You’re going to make me cry.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Before you go, I have one last question for you, and that question is: What do you wish you had known when you were first starting out with herbs?

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, my gosh. That’s a great question. I wish I knew that you don’t have to have one teacher that you agree with every single thing that they think to choose to learn from them.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Hallelujah! That’s a good one.

Rebecca Beyer:

That sounds so dumb, but I think I really struggled to find someone who was like my person in herbal medicine. I just wanted there to be that one guru that could just answer all my questions and always be kind and on the right side of everything I agree. I was like, “That’s just not—that’s a 19-year old thought,” which is when I really started studying. I really wish I had more fully embraced the tapestry of learning that I think we all have, and not been so disappointed and sad. I often felt very sad that I could not figure out how to find that one teacher and then move forward to study with them. It was—it was hard, but looking back now, I’m grateful for the journey. It’s been really a big adventure.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I can tell this is really important to you because I read through all the beginning chapters of your book, and very early, in the beginning, I remember you said something like, “This book or my way is not the sole highway.” You actively encouraged people within the opening pages of the book to seek out many voices, and so, I thought that was an interesting thing. I can see it’s a very important value for you.

Rebecca Beyer:

Totally. I always tell people as soon as you start feeling like you’re right all the time, you’re probably wrong, and I know that has always been true for me as someone who frequently needs to zoom out. One of the blessings of herbalism is it does inspire us to be in community sharing information, and the more we can zoom out and see all of the wisdom that we have to share with one another, and how that, you know, as a folk herbalist and not a clinical herbalist, I am constantly reminded of that because we have the unique perspectives of doing things versus reading about them, versus hearing about them is important, and that shared experience is really what makes, I think, herbal medicine work.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

So beautifully said. It’s been so lovely to get to know you, Rebecca, and I’m looking forward to meeting you in person in less than a month. It’s pretty exciting. We’ll be at Great Lakes together, so looking forward to that as well. Thank you so much for being on the show, for taking the time with us, for sharing about spicebush, and this beautiful recipe. It’s just been so lovely. Thank you. Thank you.

Rebecca Beyer:

Oh, my gosh. Thank you so much. I really appreciate you.

Tired of herbal overwhelm?

I got you!

I’ll send you clear, trusted tips and recipes—right to your inbox each week.

I look forward to welcoming you to our herbal community! Know that your information is safely hidden behind a patch of stinging nettle. I never sell your information and you can easily unsubscribe at any time.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thanks so much for listening. If you’re not already subscribed, I’d love to have you as part of this herbal community so I can deliver even more herbal goodies your way.

This podcast is made possible in part by our awesome students. This week’s Student Spotlight is on Jessica Muiseke in Arizona. Jessica is a mixologist at a tea shop and she joined the Rooted Medicine Circle to deepen her knowledge of the plants in her blends, and to help her team connect more respectfully with the plants they use everyday. We love seeing how she creatively brings medicine making techniques into the world of drinks that are both beautiful and meaningful. Jessica also brings a deep reverence for the Sonoran Desert landscape where she grew up, often honoring its indigenous plant life and her reflections. To honor her contributions, Mountain Rose Herbs is sending Jessica a $50 gift certificate to stock up on their incredible selection of sustainably-sourced herbal supplies. Mountain Rose Herbs is my go-to for high-quality organic spices, herbal remedies and even hard to find botanicals. They ship all over the US and have a massive selection of products to fuel your herbal adventures.

So, thank you, Mountain Rose Herbs, for supporting our amazing students. If you would like to explore Mountain Rose Herbs’ offerings and support this show in the process, you can click here.

Okay, you have made it to the end of the show, which means you get a gold star and this herbal tidbit.

Before we close, here’s a little herbal tidbit about spicebush (Lindera benzoin): This plant is host for the spicebush swallowtail butterfly, meaning its shimmering, green caterpillars can only grow up when nestled in spicebush leaves. And I love that image--a plant offering both medicine for people and a cradle for butterflies, and I’m sure a thousand other ways that it interacts with the ecosystem. It’s really a reminder that when we care for plants, we’re also tending to the unseen threads of life woven all around us.

Thank you for joining me. I’ll see you in the next episode.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.