Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

Black Cohosh Benefits, Uses,

& Surprising Secrets

Share this! |

|

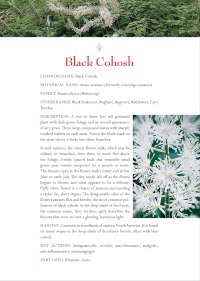

From easing hot flashes to calming muscle tension, black cohosh has long been a trusted ally for cycles of change.

In this episode, I’m joined by herbalist, author, and Appalachian plant steward Patricia Kyritsi Howell for a fascinating deep dive into one of the forest’s most mysterious and misunderstood herbs: black cohosh (Actaea racemosa). Patricia shares how this powerful woodland plant first “brought her back to herself” during a time of personal healing—and how that experience shaped decades of herbal practice and advocacy. Together, we explore the magic, medicine, and conservation of a plant that’s as beautiful as it is complex, weaving in folklore, insights from Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Patricia’s hard-earned wisdom from years in the Appalachian mountains.

Patricia recently finished updating her beautiful book on native Appalachian herbs, and as part of this interview she has generously included an excerpt from the book. You can download your copy of the black cohosh herbal monograph from Patricia’s book in the section below.

By the end of this episode, you’ll know:

► Five ways that black cohosh can ease symptoms of PMS and menopause

► Black cohosh benefits beyond its use as a “women’s herb”

► How this North American plant shares ancient lineage with herbs from China—and how it’s used differently in Western and Chinese traditions

► How to harvest black cohosh in a way that preserves (and even increases!) the plant population for future generations

► and so much more…

For those of you who don’t know her, Patricia Kyritsi Howell is a renowned clinical herbalist, teacher, and author based in the mountains of northeast Georgia. She’s the author of the newly expanded and updated Medicinal Plants of the Southern Appalachians: Second Edition, a richly illustrated guide to the use of 44 herbs native to eastern North America. A respected voice in the herbal community, Patricia supports emerging practitioners in clinical herbalism through her virtual course, Crafting Your Herbal Practice. She also leads tours to the Greek island of Crete to explore regional herbs and experience traditional Cretan cuisine.

I’m delighted to share our conversation with you today!

Click here to access the audio-only page.

-- TIMESTAMPS -- for Benefits of Black Cohosh

- 0:48- Introduction to Patricia Kytritsi Howell

- 01:59- Patricia’s Greek roots

- 09:19 - Meeting black cohosh in the wild + sustainable wildcrafting concerns

- 14:57 - Black cohosh benefits

- 30:58 - Black cohosh benefits for perimenopause and menopause

- 32:35 - Herbal preparations of black cohosh

- 33:30 - Black cohosh herbal monograph and Patricia’s book Medicinal Plants of the Southern Appalachians

- 40:39 - Pros and cons of self-publishing a book

- 51:15 - Patricia’s current herbal projects

- 55:39 - How herbs instill hope in Patricia

- 58:52 - Student spotlight

- 1:00:04 - Herbal tidbit

Get Your Free Recipe!

i

Connect with Patricia

- Website | PatriciaKyritsiHowell.com

- Instagram | @botanologos

- Facebook | Patricia Kyritsi Howell

Transcript of the 'Benefits of Black Cohosh' Video

Welcome to the Herbs with Rosalee Podcast, a show exploring how herbs heal as medicine, as food and through connecting with the living world around you. In this episode, I’m joined by Patricia Kyritsi Howell, herbalist, author, and long-time steward of Appalachian plants. Patricia shares her deep knowledge of black cohosh, a plant surrounded by both reverence and controversy. We talk about its traditional uses, the challenges of conservation, and what it means to be truly in relationship with the plant that’s both powerful and vulnerable. This conversation is wise, grounded, and full of insights about caring for plants and people alike.

If you enjoy this episode, please sign up for my weekly newsletter below, and don’t forget to stay tuned until the very end for your herbal tidbit.

Tired of herbal overwhelm?

I got you!

I’ll send you clear, trusted tips and recipes—right to your inbox each week.

I look forward to welcoming you to our herbal community! Know that your information is safely hidden behind a patch of stinging nettle. I never sell your information and you can easily unsubscribe at any time.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Patricia, welcome back to the show. I’m so excited to have you here.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Hi, Rosalee! Good to be here again.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

So, just as we are getting started, it is starting to rain here. This is not big news where you live in the Appalachia, but where I live, this is big news because I live in the desert, and I just feel like I’ve just entered—like you have brought the moisture. I feel like, “Okay, I’m just going to pretend that I’m in Appalachian forest right now.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

I’m happy to moisten things up for you.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thank you. Thank you so much. Well, I’ve had you on the show before. We got to hear your herbal story. Now, I’m just wondering what have you been up to since we’ve seen you last?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Well, I finished writing a book—redoing my book, which I know we will get to in a minute. That was what I was working on for the last year, finished it in March, and then I immediately got on a plane and went to Greece for a month, as I have a small tour company that I do these eight-day tours in Greece that are focused on herbs and food, basically. A little bit of hiking. People ask me, “How much do you hike?” I say just enough to justify how much we’re eating. You know, a good balance.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Perfect, yeah.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

That’s really a place that really restores me, so being there for a month was wonderful. Now, I’m just kind of lying low for the summer. I would never say that I’m retired, but I definitely—I closed my school officially completely at the end of last year, and took down the website. That was a big chapter ending because I’d had the school here in Georgia for 30 years. It was kind of sad and also a huge relief.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, yeah, both, and like you said, what a major new chapter to just—I don’t know. I imagine your calendar looks very different once the school closes.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah, it does, and you know—I know that you do a lot of teaching too. There’s something about—I would usually have between 26 and 30 students in my ten-month program, and so just kind of the whole process of holding space for a group of students for ten months, it takes a lot of concentration and intention, really, to hold that together. I loved it and I would not have changed a minute of it, but I’m also okay that it’s not happening anymore.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Ready for a new chapter.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah, I mean, I think yes. As for me, as I get older—I think when you’re younger as an herbalist—and this was definitely true for me—I just wanted to know everything and do everything, work with every plant, and make every tincture. It was like nothing was too much. Now, not that—I wouldn’t say I’m cynical or jaded about it, but I feel like, “Okay I did that. I found out what I needed to find out, and I had that experience.” It’s kind of nice to let up on the gas pedal a little bit.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, and then go spend a month in Greece. I’d love to ask you some questions about that if you don’t mind.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Sure, sure.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I know you have family roots in Greece. In fact, your book was dedicated to your—I want to say, grandfather? Yes. Here we go. Is that the Greece side of things?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah, that’s my dad’s side of the family, so—and just as a little sidenote, my name, my last name growing up my whole life was Kyritsi. When I went away to college, I just wanted to have a waspy name because if you have a name like that, you have to spell it every single time, and everyone mispronounces it. I know you have a name story as well. When I was getting ready to go, my mom’s side of the family was Howell. My Grandma Howell said, “Why don’t you use Howell? Because I would be proud to have you be a Howell and everybody knows that name. ” This was back in the ‘70s when you could just go into—I had a passport in that name. I never legally changed it, but it was so easy to just have a name that people would—you didn’t have to spell it. Then, about 15 years ago, I realized that I was really—I would really have trouble proving who I was because I had a birth certificate with one name, and a passport, and driver’s—anyway, so, I legally changed my name to that so that—that’s where that name comes from. My grandparents emigrated from Greece in the early 1900s. I still have—my grandfather was one of 12 children, so I have like a million cousins in Greece, and some in the United States, but I—it’s really a place that I love so much.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Do you have a favorite—you mentioned food and justifying it—just enough hiking to justify the food. Is there a favorite dish that you have or a couple? I realize it might be hard to choose one.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Whatever is in front of me is usually my favorite.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Alright.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

There is one dish that people make there in the spring. I always go to Greece in the spring because the plants all kind of die out as the weather gets hot, and then in the summer there’s really nothing herbal to look at. It’s called “Aginares à la polita” and it means “city style artichokes.” It’s artichoke hearts with new potatoes, young carrots, a lot of dill, and then kind of a lemon sauce that goes on it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It sounds amazing.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

It’s like a very light summer stew, almost; kind of on the edge of that. I love—I love artichokes and dill, so that combination. I did eat a lot of that when I was there.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Artichokes are my favorite vegetable, hands down, my absolute favorite, followed maybe by eggplant, and then possibly celery. Artichokes are my favorite. We don’t get really good artichokes where I live. When I go to Europe, Europe just has much better artichokes, so I’m always trying to find them while I’m there.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

In the spring on Crete, you’ll just be driving down the road and there’ll be a guy parked on the side of the road with a pickup truck full of artichokes, a little scale, and some bags. You just pull over. When I tell my friends and family there that an artichoke here can cost $4 or $5 just one, the big globe artichokes, they’re just like—they don’t believe me.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It’s $7 at my local store for an artichoke and it looks like crap. I can’t even—it’s my favorite vegetable so I would justify it if it looked good, but it just doesn’t, so I’m like I can’t pay $7 for a crappy artichoke. It would just-

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

You need to come with me to Crete because we can gorge ourselves on artichokes.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s becoming very clear to me right now.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

It looks like you have Greek tendencies.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

So, you’ve been in Greece. You’ve been hanging out, school closed, and the book. The book is just absolutely beautiful. We’re going to dive into it, but before we get there, I would love to talk about your chosen plant, which I will admit was highly suggested by me, which is black cohosh.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

You mean, you’re twisting my arm and saying, “Whatever you want to talk about, as long as it’s black cohosh?”

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Pretty much.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

It doesn’t take much encouragement because I do love the plant myself.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I often say, “Why did you choose black cohosh?” but you didn’t really. I did. So, let’s talk about why you love black cohosh and wherever you’d like to begin.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

You mean why did I agree?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, why did you agree.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

When I first came to the Southern Appalachians, which was in the ‘80s, that was way back when I was a sound engineer and I worked in the music business, and I came here to do an event. I knew about herbs at the time, but I wasn’t—I didn’t think of myself as an herbalist, just sort of an enthusiast. I remember hiking and stopping on a trail, and looking up the hill and seeing—all of a sudden, I was like, “Oh, my God! There are hundreds of black cohosh plants on this hillside.” It just took my breath away because I had gone to school at the California School of Herbal Studies, so very different climate. I think we had three black cohosh that sort of struggled because it didn’t get that cold, and it does like cold weather. Just to see it so abundantly was thrilling. That’s when you know you’re an herbalist--when you see a plant in the wild and you kind of, “Ah! There it is!”

Over the years, I know it so intimately because it grows all around me where I live here in the Southern Appalachians. It is a—it’s just a lush, beautiful plant. It’s blooming right now. It’s kind of at the end of its blooming time. One of the things I write about in the book is that one of the common names for it is “fairy torches.” When you see it in a deep forest where there’s such a large tree canopy that everything is in shade, it does look like something being illuminated from the base because you’re in this dark, green environment. Way back there, you see these white plumes in the dark and they do really look magical in that setting.

It’s also a plant—one of the other things I really like about it besides its use, its application as a medicinal plant, is it’s something that you can really harvest sustainably, by—because it’s the root that we’re using, the rhizome and the rootlets, but it grows with an underground root, so when you dig it up, there will be a stalk that is the growth to this year’s plant, but then right next to that in the rhizome is the bud for the following year’s growth. When you collect it, if you cut the first couple inches off the rhizome and replant it, it will regenerate the next year. It might not flower. It might take a couple of years still for it to flower.

There are places here—I have access to some private land where I can take my students for harvesting. We’ve been harvesting—I’ve been here over 25 years, and going back to the same places with my students over the years, and there’s even more now as a result of us harvesting it and replanting it. We always have that conservation concern with medicinal plants, but with black cohosh—I mean, for personal use. Now, I know that I talk to people in North Carolina, like Jeanine Davis at the University of North Carolina, who has done a lot of work on woodland medicinals, it’s still being harvested quite a bit in the wild for the commercial market. I think it’s on the watch or the endangered list for UPS. I forget which category it’s in, but regionally, it’s very abundant. I tell my students and I write about this in the book, it’s like if you’re doing commercial products that you’re selling, then you need to work with a grower. If you’re harvesting four roots for yourself, I think that’s appropriate wildcrafting use of the plant, but I think it’s when people are doing so much and then they’re making product and sell it, for me, that sort of flips to a different category at that point.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

If those sustainable harvesting methods that you described aren’t being used, that’s ultimately, the problem there, if it’s not done in a regenerative manner.

I love the fairy torches. I can only imagine. I’ve never been to Southern Appalachia. I’ve never seen black cohosh growing in its native habitat before. I do grow it myself and love it for that, but I can just imagine that growing in a darker forest, and those light torches coming up, that’s beautiful. It’s an easy plant to fall in love with simply because of how beautiful black cohosh is. I’ve always found its medicinal applications to be interesting because it’s really well-known for a couple of things. I don’t know. It seems they don’t necessarily go together in some ways, I don’t know, but I’ll let you talk about it, just how you might work with this plant.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

This is a good—this plant is a really good example of something that I always talk about, which is “botanical disjunction.” You familiar with that term?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

No, I’m not.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

This has to do with—now, we’re getting into talking about major geographical earth changes over millions of years. When those numbers start up, I can’t go with them, but a long time ago—let me preface it that way—there were—there was a plant community that extended from eastern North America over land bridges into what’s now Northern China. For that reason—excuse me—a lot of our plants here are also found growing in China. When the glaciers came down, they scraped away a lot of the plant life, but there were some pockets where the mountains were so big that the glaciers stopped, and Southern Appalachia is one of those places. There are also a couple of places in the Ozarks, and then Northern China, where those plant populations survived glaciation, and then after the glaciers receded, they expanded again.

When I was studying herbs to begin with, more of a Western approach at the California School, and we talked about herbs like black cohosh, we were really looking at it more from what the eclectics said about black cohosh and what they learned from Indigenous people in North America, and that mostly has to do with the female generative system, using it as a preparator for labor, for menstrual cramps, a little bit of rheumatism, things like that. But in the ‘70s when Nixon went to China and we began to have cultural exchange with China, and that’s the point when acupuncturists, and acupuncture, just in general, became known to us here in the United States. One of the things that all the hippy herbalists realized, of which I was one—I still am—my sister said—I have a sister who is very much younger than me. She said, “You don’t have—you never have to say ‘old hippies,’ because if you say hippies, it’s implied.” It was a while ago.

Anyway, one of the things that we realized at that point is that what was being used in Traditional Chinese Medicine, herbally, were the same plants that the Cherokee and the other Indigenous people have used in North America. When I finished herb school where I studied with David Hoffmann and Amanda Crawford, it was very much a body systems approach with some energetics. I practiced for a few years. I felt really frustrated by the mechanistic aspects of it. Now, if I had maybe done a deep dive into more of the eclectic approach to herbalism, I wouldn’t have felt that limitation, but I kept seeing patterns with my clients of different emotional states, different personality types associated with specific health issues, and so I just couldn’t figure out a way to put those two pieces together based on my training. It was around that time that I met Althea Northage-Orr who is an acupuncturist, herbalist, genius who practices in Chicago. When I met her, we started talking (as herbalists do) about herbs. What we realized is that she knew all the plants if they were in a jar with a label, and I knew them all if they were in a garden, but if a person sat in front of me, I really struggled to put the plants with the person. She wanted to know more about the plants. Anyway, being entrepreneurs, that’s how we started our school in Chicago for herbal medicine in 1991. Basically, we were doing it so that we could learn from each other and let our students pay us to do that, but don’t tell anyone.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Just between you and me.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah, but when I kind of studied with Althea and learned from her as my mentor, I began to learn how in Traditional Chinese Medicine, a lot of the herbs were used that I was already using, and one of them was black cohosh. The indigenous use of the plant had a lot to do with the female generative system and rheumatic pain, joint pain, but in TCM, it was also used as a bronchial antispasmodic. It was also used to push pathogens out of the body at the early stages of a pathogenic invasion. In TCM, they would call that something like a surface-releasing herb. So where we might think of taking Echinacea, something that stimulates the immune response, in that paradigm the idea is to get all the pores of the skin to open up and let everything get flushed out because the surface immune system is battling at that point to keep things out. Black cohosh is one of the herbs that they use. It doesn’t necessarily prevent someone from getting sick, but it usually tends to increase the pace at which an illness goes through all the stages. Whereas, somebody might get a cold and be sick for two weeks, when you’re using these more diaphoretic surface-releasing herbs, everything happens condensed. So, you have a couple of days of feeling like, “I’m getting sick,” and then you have a day or two of feeling really bad, and then you have a little lingering cough, and then it’s over. Black cohosh is one of the plants that is used in that way in TCM. But also, because of what I learned, I started including it in my cough syrup formulas, and found it was really, really effective because ultimately, it’s an antispasmodic for tubular parts of the body, so that would be the uterus, in general, and the bronchials. And then it has a lot of calming qualities as well.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, we work with five phase theory—that there’s relationship between different organs, and it’s kind of a way of talking about how energy moves. What I observed—I’m not saying that I’m the only person who thinks this—but what I observed is that the wood element which is—governs the function of the liver, has a tendency to get overextended. It gets—and that’s when women experience things like premenstrual syndrome, it’s a case of liver excess. The liver is really ungrounded. You can’t sleep. You can’t think. You can’t digest properly. You feel really, really ungrounded. The element that comes before wood is water. What I observed is that what black cohosh does, when we talk about it in the context of hormonal imbalances, is that what it does is it really grounds the wood element in the liver in the cooling, grounding aspects of the water element. So, it helps—when someone is a wood excess type or when someone has severe PMS, it’s like they usually feel really irritated and they have trouble accepting nurturing and—what do I want to say? Besides nurturing, help, in general. They’re just kind of flailing around.

I am an expert on PMS because I was involved in a years-long clinical trial—in my own clinical trial of having severe PMS. It is one of the things that was a catalyst for me to know about herbs because I wasn’t getting any help from conventional medicine, and it was really disrupting my life. Black cohosh was one of the herbs that kind of brought me back to myself. Instead of—one of my friends calls it “being in your ninth chakra or tenth chakra.” You’re like so up here but you’re not in your body anymore, and that’s how I always felt. I noticed that black cohosh—and it’s a root herb, so it kind of makes sense that it put me back here where I was like, “Okay. I can think clearly now.” In my clinical practice, I often use, actually, black cohosh combined with motherwort as one of my primary acute formulas for menopausal irregularity, menopausal insomnia, anxiety, brain fog, and also, for premenstrual issues. And then because it’s an antispasmodic, it also helps with cramping and things like that. I think when you have this visceral experience of being healed by a plant yourself, then you can become an advocate for its use in a way that you can’t if you’re just reading about it, right?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

If I tell you this is what this plant does, but you’ve never had it happen for you, it stays a little abstract. The plants that I feel really passionate about are the ones that have come to my rescue. Black cohosh, definitely, was one of them.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I think it’s like if you’re introducing someone, it’s very different to introduce your best friend versus introduce someone you met last week, for example.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Exactly. You’ve heard about them, but-

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Exactly. So, I have a lot of affection for the plant. It’s also, like you said, it’s just one of the most beautiful plants. It’s interesting too that in its native habitat, the plant almost always grows with blue cohosh. All the places that black cohosh grows here in abundance, there’s an equal amount of blue cohosh there too. Then that brings up just that age-old question of, “How did people know to take these two plants, both with the common name ‘cohosh,’ and combine them for this very specific purpose?” I think that’s something that I just sit around and think about a lot like, “I didn’t know this. Where did this come from?”

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Because—correct me if I’m wrong, but those two are not botanically related. Is that right?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

No, no, no. How they’re related is they grow in the same plant community, really, that’s it. And the roots. The roots look different. The foliage is different, everything about them, but they’re both understory plants. They’re both on the forest floor, two or three feet tall, and bloom at different times. Everything about them is different, other than that.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

You said they—that those two are combined a lot. Will you speak to that a little bit?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah, that’s a really, really common—not used so much anymore, but it was a really common herbal formula, 50/50 of each of those to give to women during the last three weeks of pregnancy as a uterine tonic, and then also, in higher, frequent doses to promote labor because when those two herbs are combined, what they do is they’re responsible for therebeing rhythmic uterine contractions. Two of the things that can really be dangerous in child birth is stalled labor, and then if the uterus is spasming and contracting too rapidly to be productive. Black and blue cohosh together were used traditionally for that purpose. Now, in the last—I don’t know, maybe 15 or 18 years, I think—there have been reports of babies being born with congestive heart issues, and there is some suspicion that it’s related to blue cohosh use at the end of pregnancy. A lot of the midwives that I know now use black and blue cohosh as homeopathics during the last three weeks to avoid the potential that there’s something in blue cohosh that’s doing that. I don’t know if any really specific studies or clinical information is being gathered because one of the problems, of course, that we have in the United States is that herbalism is not considered scientific. There’s not a lot of research going on about the therapeutic actions of herbs in this country. Most of it is happening somewhere else. I don’t know if anything has been done further. I haven’t really followed it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Do you happen to know the etymology of cohosh? I’m just wondering.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

No, I don’t. I’ve heard different stories that it was the Creek. It was the Cherokee. It was the Menomonee. It was the Ojibwa. I don’t know who used those names. And then they have the same names because they were combined so frequently together, the cohosh.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I see.

Hey, it’s Rosalee. You know, creating this podcast has been one of the most rewarding parts of my herbal work, and if you found something meaningful here, whether it’s a new perspective, a favorite recipe or just a sense of calm, I want to let you know there’s a good way to go even deeper. It’s called the Podcast Circle. Inside you’ll get access to live classes taught by some of my favorite herbal teachers, behind-the-scenes updates, and a beautiful library of herbal resources that we’ve gathered over the years. But more than that, it’s a space to connect with fellow plant lovers who care about the same things you do. And truly, your membership helps make this podcast possible. It’s how we keep the episodes coming and the herbal goodness flowing. So, if you’re ready to be part of something more, something rooted in connection, head over to HerbalPodcastCircle.com. I’d love to see you there.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Black cohosh is also often used to support people through perimenopause and menopause, as well. I know you speak to that in your book. I wonder if you could mention that a little bit as well.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Well, I mean, first of all, there is some—we know how dangerous information is on the internet, but it is sometimes talked about as being something that has hormonal properties, which it does not. I believe that what black cohosh does is it regulates not in a hepatic way, but it has some sort of impact on the liver and the way the liver goes out of balance, in terms of its effect on the nervous system. Black cohosh helps with a lot of—a lot of what women experience in menopause, which is brain fog, problems with memory, trouble getting good quality sleep; not so much hot flashes, I don’t think, but that just sort of ungrounded. Again, that’s really kind of the theme, I think, of that. I know that a lot of the women that I worked with over the years had really good results using black cohosh as a sleep remedy, and taking it throughout the day along with some other things that we already know really help with cognitive function, like bacopa, for example, or gotu kola to kind of just sharpen the pencil is how I think of it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It’s a nice way to think about that. When you’re working with black cohosh, are you often working with it as a tincture or will you do a decoction as well?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

You know, I pretty much used it as a tincture or a capsule, not because it has a horrible flavor or anything, but there were people who I worked with in my practice who wanted to get in there, roll their sleeves up and mess around with herbs, and then I seem to have a greater number of people who wanted convenience, and that was part of what helped them comply with the protocols I gave them. Occasionally, yeah, black cohosh as a decoction because that would be how we would prepare it, as a water extract, but I used to make a lot of it into tincture and used it primarily that way.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Nice. This is from your book here, black cohosh. You have a whole chapter on black cohosh, which you’ve also shared with us so folks can download this sample chapter from your new book above this transcript. In this, you have 44 herbs in this book? Is that correct?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

They all have a similar structure. We’re looking at the names. We’re looking at the botanical description, habitats. We’re looking at medicinal aspects, preparations, and then parts about harvesting too. The photos in this are just so stunning. If you can tell, it’s a good size book as well, so you get a really good look at the photos. I’ve been looking at this book, looking at so many different plants within here. It didn’t take me very long to go to the back of the book to see who is taking these gorgeous photos. As a semi-amateur photographer myself, I wanted to know, and it was really cool to see you have the bulk of the photos on here, as well as folks here and there, as well. It’s absolutely lovely. I love a stunning book, and this is an absolutely stunning book. There’s lobelia.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Oh, yeah. I’m sure that a lot of your herb audience—when I look at my phone, the pictures in my phone, it’s plants, plants, plants, plants, flowers, plants, plants, plants. So, when I was getting ready to—because I had published this book originally in 2006 without photographs—because at that time, doing self-publishing with photographs, what was really hard to do. It really wasn’t something that was readily available. I had this dream of someday my dream book would have these big pictures in it. I think I was taking pictures in anticipation for 20 years for these things, so when I sat down to see “What pictures do I need?” and then looked at my pictures that I had on my computer, I was like—I was actually very surprised how many I had. I really tried to—one thing that I think can be frustrating if you’re trying to identify plants in the wild and you have a field guide, is that they’re only pictures of plants in flower, so if it’s not flowering, it’s a little tricky to see like, “What is this?” in August, as opposed to in the spring. One thing I really wanted to do was have an herbalist’s approach to the photographs and show things in the fall or show things early in the spring, show them as their flowers were blooming and fading, and try to do that lifespan of the plant, as opposed to when it was all-smiling-for-the-camera kind of thing.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Here’s a smiling passionflower, maypop, Passiflora incarnata. So, we have the beautiful aspect and then you turn the page, we’ve got the fruits. We’ve got the leaf, so like you’re saying, you got it all. You got the pretties and the functional.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

I wanted it to be useful for people who are just getting used to what those plants look like, definitely.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

When I saw this, I was surprised. I didn’t realize you all had pipsissewa down there. It grows here too.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

You have it there?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

It’s pretty common here. In fact, the pictures that are in there are the pipsissewa I took last spring while I was working on the book. There’s a place that I walk at a state park near my house. When it was in bloom, the plant is only this tall—for any of you listening who don’t know it—so I had to lay down on my stomach and get the thing. People who were walking by on the trail were like, “Are you okay?” as I was trying to get a really good close up of it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

This is normal in the herbal world.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah, yeah. Nobody thinks twice about it. Not to—I’ll just jump in and say, one of the things also that I put in the book that I think is especially helpful is a bloom and a harvest chart at the back.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I saw that.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

It’s kind of geared towards this region, so I don’t know when pipsissewa blooms for you. For us, it’s pretty early on in the spring, but I wanted to give people a range of when to look for those plants if you were going to harvest them.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It’s interesting you mentioned that the black cohosh is at the end of flowering right now, which we’re recording this at the beginning of August. That’s the same for my garden. It’s towards the end of flowering right now. It was interesting to me because we live in very different climates. One thing I want to say—oh, go ahead.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

I was just going to say, like most roots, we wait til the foliage is starting to almost die back in the fall. Actually, I sometimes—now, I know where it’s always growing, but when I was harvesting it in different places, I would put yarn around it so that when it was a hard frost and it got knocked down, the foliage got killed by the frost, I could still harvest the roots because the later you wait, the better because more of the potency of the plant is now in the root.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s clever. One thing I really want to say about this book is—it’s Medicinal Plants of the Southern Appalachians, which someone might immediately think, “Oh, I don’t live in Southern Appalachia.” The plants in this book are the plants that we work with. There are very few that are super specific. There’s boneset, black walnut, blackhaw, evening primrose, gentian, goldenrod, jewelweed. There are just so many in here that, like I’m saying, grow where I live as well, so I love that aspect about it. The photos, the feel of it very Southern Appalachia, and I think folks all over can really appreciate it. If you want to learn about herbs from a variety of different habitats and everything, this is going to be a fabulous book for that. Solomon’s seal, just saw that one.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Actually, one of my semi-retired herbalist habits now or pastimes is drawing plants and doing botanical drawings. I just finished—it’s downstairs—a Solomon’s seal that I was really happy with.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, lovely. That’s fun. I would love to ask you a couple of questions about self-publishing. This book is self-published like your first one, and what does that look like? What—even just like your process because I think it’s interesting to know how much goes into a book. I know you wrote the original years ago. You spent at least a year, if not more, updating it.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

The original book is—I thought I had some copies of it right here—was basically the handouts from the courses I taught at my school, the BotanoLogos School here. The longer you work with plants, the more you know about them. Actually, when I went back and looked at the first edition in preparation for redoing it, it was kind of a humbling experience because what I thought I knew about the plants in 2005, and what I know in 2025 and 2024 was—there’s no comparison. My ego took a big hit thinking about people having read that first version that I had so much more I could add to it.

I’m really a big advocate for self-publishing, if you have the energy to do the work, do the self-publishing. I feel—you’ve written a lot of books and had them published, right? I think you’ve gone with a publisher for most of your books.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I just self-published this year though, so I’ve had both experiences now.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Oh, you did? Okay. What book was that that you just published?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

It was actually a bioregional coloring book, which is a little bit different sort of thing. Because it was so bioregional, it just kind of made sense to work with the local folks to get it out there.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Sure, sure. First of all, you have to be very self-disciplined to keep working on it. That’s the hardest thing, I think, but I wanted—when I wrote the first version of the book back in the early 2000s, the University of Georgia heard about it and I teach down there for some time, or I did at that point. They said, “When your manuscript is done, we’d like to have first rights for it,” and so when I finished it, I sent them the manuscript. They got kind of cold feet because they wanted scientific citations for all the uses of the plants. I tried to explain to them that there weren’t for many of them because they just—plants that have been used traditionally or in folk medicine, but not anything really double blind studies or anything that they would find legitimate. They were very nervous about it, then they came up with this kind of crazy recommend—suggestion, that I find somebody who had a PhD who would sign on as my co-author that would give it more academic credentials. I said, “Can I have that back?”

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I can tell you loved that idea.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

I kind of pouted for about six months and was really discouraged, and then I took a seminar with somebody about self-publishing. It was a man named Tom Bird, who is out of Arizona, who was teaching at Emory University in Atlanta. I showed him the manuscript and he was like, “Don’t ever give this to a publisher because you have a public platform.” I think that is one of the things about self-publishing. If you have some sort of public persona, you teach or you’re known in some way, that it makes sense to self-publish because you have something to help you with promoting it and selling it. You already have—you’re already considered sort of an authority on that topic. If you’re a bank teller and you write a book about herbs, probably better to go with a publisher because they’re going to promote it for you and do all that. He really inspired me, and that’s what—I used what I learned from him to do the first book, but I really just didn’t have the money to do it the way I wanted to as a self-publishing thing.

During COVID, like many people, I was like, “If I live through this, what am I going to do? What are my life priorities?” because we all thought we were going to die. I think, at least, I did. I was like, I ate whatever I wanted. I was like, “This is the end here.” On my list was: redo the book with photographs. I want that. I want to make that contribution to herbalism – that I took all of what I’ve learned in the last 30 years here in the Southern Appalachians, and put it in some way that where after I’m gone or if I still want to teach anymore, people have access to it. I also think that—I wanted the complete control over content. I wanted to be able to make really specific recommendations for uses and dosage, and things like that. It’s a hassle. You have to get an ISBN number. You have to get a Library of Congress number.

With the new book—I mean, with both books, I hired a book designer, but the book designer that I hired to do this book was very experienced and expensive. She was an artist, so I thought—I felt like she took my vision and brought it to life. We got very close. We collaborated, Barbara Landy is her name. She lives in the Bay Area. I was really fortunate, but I also had to invest in the book and that isn’t always what people can do.

The way that I learned how to do self-publishing was using a specific printer—printing company that is owned by Ingram that is the major distributor of books to bookstores in North America, and throughout the world, really. They do book distribution everywhere. Because the printing company that I use is owned by them, as soon as I uploaded the PDF of the book to their website to have it printed, it automatically was in the Ingram database, so that someone can go into any bookstore and order the book. They also automatically put it on Amazon and Barnes & Noble, and all the places that they promote their catalog. I have other friends who have self-published, who had to get it on all those places themselves. They had to get it on Amazon. They had to get it on Barnes & Noble, or they have a lot of them in their basement and they’re shipping them themselves. I don’t have that. Anybody can go order the book and have it shipped to them. I can order the books wholesale and take them when I do speaking engagements.

I had a lot of help. I had a couple of colleagues who did technical editing for me, which you really need somebody to—who’s got an herbal background to look at what you’re saying and make sure that you don’t start talking about roots, and then switch to leaves halfway through the recipe or something like that. Editors are worth their weight in gold, as you know. For me, I’m a project person. I like a project, so I was challenged by it and I like doing it, but I think all my friends got really sick of hearing me say, “I can’t go because I’m working on my book,” and like it was never going to be done because pretty much all of 2024 and through March of this year, that’s all I was doing. It was a luxury that I was at a point in my career when I could step away from teaching and just devote myself to putting the book together. I was also—I really wanted my book to be only plants that are native to the region. There are some other books about medicinal plants of the Southeast, in general, but they have plantain and dandelion and chickweed. I was a purist. I wanted it to be like what was here 300 years ago, and what were those plants.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Again, it’s absolutely stunning. I was going to ask you what is the best way for folks to find the book. So, you’re just recommending wherever folks like to buy books, go in and order it.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Wherever they like to buy books. I do sell it through my website.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Will you share your website with us?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

It’s my name.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Alright, Patricia Kyritsi Howell. We’ll make sure to put that in the show notes. Oh, wild ginger too! I just think of that as a redwoods plant.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Oh, really?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

This plant—I know I have a friend in—who lives in Arizona. Oh, no, not—who was it that—Phyllis Hogan who lives there. I think she’s Arizona, isn’t she?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

She is, yeah.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

She said she has black cohosh growing all around her, which shocked me because I didn’t think that our plants went out that far west.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah, that is surprising.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I just interviewed Phyllis Light and she said that ginseng, American ginseng grows in 39 states. I had no idea.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Wow.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I need to get out more. Before you go, first, is there anything else you’d like to share about projects you’re working on? It feels like the book has been pretty all-encompassing, it has taken up a lot of your focus.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yeah, I’m still recovering from that. I’m still taking groups to Greece. I have a little tour company, so I have people going to Greece. I’m doing a lot of botanical drawing. Kat Maier and I have our course that we teach called “Crafting Your Herbal Practice,” because one of the things I think of as I have accumulated years of experience as an herbalist, is wanting to help other young herbalists who have invested a lot of money in their herbal education, and now, they want to help people and they’re really passionate about it, but maybe they don’t have any kind of entrepreneurial skills or don’t really have the lay of the land of what’s required to really do a practice in a way that doesn’t burn them out, and doesn’t come across as chaotic to their clients. Once you take the position of putting yourself out there as a practitioner who is working with people and establishing that therapeutic relationship, there’s a whole array of things that are involved with making that safe for them and for you. A lot of the work that I’ve done in combination with everything else has been mentoring people, but then a few years back, Kat and I got—had this conversation of why don’t we combine what we’ve both learned and package it in a way that helps people not have to do what we did, which is recreate the wheel. That is another project that I have that’s a virtual course, and it’s great because I can do it right here.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I’m so glad you mentioned that. I’ve talked to several people who’ve gone through that and found it just extremely helpful, kind of like you’re saying, bridging that gap between school and practice. I love the collaboration. It reminds me of your story of working with Althea, working with Kat. It’s just a beautiful thing when minds come together and support each other in complimentary ways.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

We have Emily Ruff as one of our guest teachers, Camille Freeman, and Mimi Hernandez, who are all [crosstalk]

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Quite the lineup.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Huh? Yeah, quite a lineup. Yeah, yeah. I just really—we need more herbalist, and that’s kind of what my motivating factor right now. It’s like I don’t want people who are passionate about herbalism to either make a misstep in their practice that damages their reputation because they didn’t keep confidentiality, or they didn’t know what to do if somebody had a bad reaction to an herb. There’s a lot of things like that that I think slip through the cracks of most herbal trainings. I know, for me, when I trained extensively at the California School it was a great program, great teachers, but I didn’t really understand how to have good boundaries as a practitioner or how to do pricing. I think a lot of herbalists too, feel guilty about charging for their services, and as a result, they’re poverty stricken or they never have a successful herbal practice as a result. I like to encourage them to take themselves seriously because if they have a solid financial foundation for their practice, then they can do things like mutual aid, sliding scale, and free consultations, but I don’t think you can start out doing that if you want to have a place to live and something to eat.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s exactly what I say: Don’t start there. Get your feet under you first, and then the rest will come. Thank you so much for sharing this, sharing your project, sharing your book, sharing about black cohosh benefits. I really appreciate it. I’m so glad you’re back here on the show. It’s always a pleasure to get caught up. Before you go, I’d love to ask you one last question.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Alright.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

And that’s, how do herbs instill hope in you?

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Well, it’s heavy lifting these days, but I think the way herbs instill hope in me, at this point, is that their ability to calm us down and allow us to think clearly and assess things clearly. I think that a lot of the—a lot of people in my community and a lot of my friends are really struggling with anxiety and feeling hopeless and depressed these days. I do think there are herbs like mimosa and rose and motherwort, hawthorn that really help the heart and keep people from feeling disempowered at this time. I also think that as healthcare challenges and access to healthcare seems to be changing, and people maybe can’t do as much with insurance and things like that, or Medicaid, or whatever they use to rely on, that as herbalists, we’re right there to help them see that that doesn’t mean that they don’t have any support or there’s nothing they can do if they can’t go to a conventional medical doctor. That gives me great hope.

Even though I’m not technically practicing anymore, as you know, I’m sure a lot of the people listening to your podcast know that once you tell someone that you’re studying herbs or you know anything about herbs, you start getting questions. I still get emails and phone calls and people stopping by asking for help, and that’s where I’m encouraging them to do things like make nervine tonics part of what they do every day, so that they don’t get so freaked out that they’re immobilized and they can’t take action to support the freedoms that are in danger right now.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s beautiful. It’s turning to the plants for support for empowerment and groundedness – things we desperately need, as you’re saying.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

Yes. Rosalee, it’s always an honor to be on your podcast. I’m a great fan of yours and the work you do, and how much information you make available out there, so thanks for including me.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Absolutely. It’s always a pleasure. Thank you so much.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell:

You’re welcome.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thanks so much for listening. You can download your black cohosh monograph above this transcript. And if you’re not already subscribed, I’d love to have you as part of this herbal community so I can deliver even more herbal goodies your way.

Tired of herbal overwhelm?

I got you!

I’ll send you clear, trusted tips and recipes—right to your inbox each week.

I look forward to welcoming you to our herbal community! Know that your information is safely hidden behind a patch of stinging nettle. I never sell your information and you can easily unsubscribe at any time.

This podcast is made possible in part by our awesome students. This week’s Student Spotlight is on Kate Vitale in Wisconsin. Kate has taken nearly every course we offer from Rooted Medicine Circle, and the Herbal Energetics Course, to Cooling Inflammation, and more. She has been an active, encouraging presence in them all. She asks really thoughtful questions. She shares her discoveries in real time, and something I love, she always takes the time to cheer on her classmates. In her reflections, Kate described how her sit spot, a creaking swing overlooking the river, has become her place of solitude and inspiration. She also shared about her deep connection with her plant ally, calendula, saying she played with it, loved on it, talked to it, and harvested galore. Her enthusiasm for learning and her generous spirit brighten every space she’s a part of.

To honor her contributions, Mountain Rose Herbs is sending Kate a $50 gift certificate to stock up on their incredible selection of organically and sustainably-sourced herbal supplies. Thank you so much to Mountain Rose Herbs for supporting our amazing students. And if you’d like to be an herbalist, you can explore my foundational courses at herbswithrosalee.com.

Okay, you have made it to the very end of the show, which means you get your very own gold star and this herbal tidbit.

I’ll have a little black cohosh story to share. A few years ago—many years ago now, actually, I planted some black cohosh right outside my front steps thinking it was the perfect spot because it was close to a water spigot, so I could keep it extra hydrated in my dry climate. I imagined those tall, flowering fairy wands of flowers just greeting me every time I came and went. What I didn’t realize is that black cohosh flowers smell like death and decay, so for weeks, when it first started flowering, I kept catching this awful odor and I just thought—I really thought something was rotting nearby. But eventually, I figured it out. It was the lovely black cohosh. So, while I still admire its beauty, I’ve learned it might not be the most welcoming plant to keep right by the front door.

As always, thanks for joining us. I’ll see you in the next episode.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.