Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

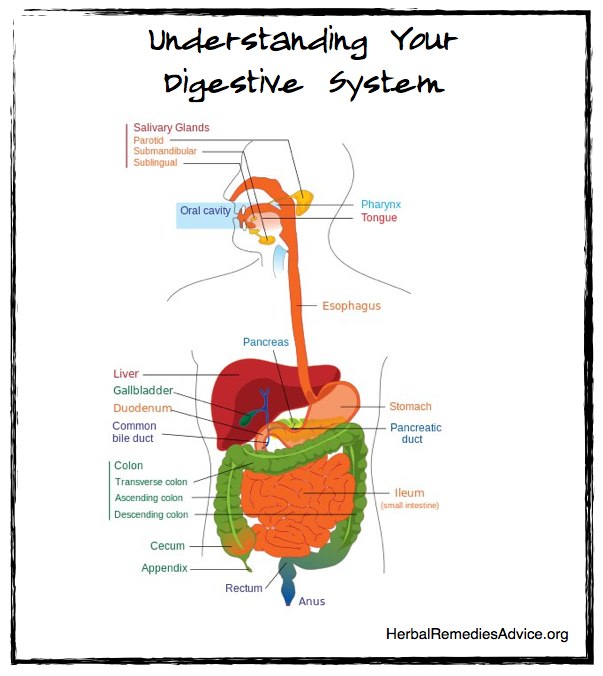

Digestive System Anatomy

Share this! |

|

This article looks at the digestive system anatomy so that you can better understand the process of the human digestive system.

Your digestive system is an incredible machine that is designed to take in whole foods and then extract vital nutrients that will then be transformed into energy and building blocks for your entire body. It’s pretty amazing to see all the steps involved in the digestive system anatomy.

The Digestive System Activity

(Or A Day in the Life of Your Food)

The digestive process can start even before you take your first bite of food. The smells and sights of delicious food can start the digestive process by promoting salivation and other digestive enzymes. The digestive system continues with the voluntary action of the intake, chewing, and swallowing of food.

Normally your salivary glands produce just enough saliva to keep your mouth moist but, even before the food hits your tongue, your salivary glands are hopefully secreting extra saliva. About 1 to 3 pints of saliva a day is produced in the mouth; you can have too much or too little. Saliva is mostly made up of water but also includes special enzymes used to break down starches and sugars. The salivary reflex is started when you smell delicious food or eat sour or bitter foods.

We’ve all heard that we need to chew our food well (so you do right?). Chewing or mastication is a very important first step in changing the food into smaller molecules. It also allows for the mixing of saliva with the food to further break down starches and sugars. Besides saliva, your tongue, teeth, and gums all play an important role in this mastication process.

Once you’ve swallowed your hopefully well-chewed food (called the bolus), it enters the esophagus. The esophagus is lined with muscles and the involuntary muscle action of peristalsis helps to move the food down to your stomach. This means that you could hypothetically eat while standing on your head, although such an action is not advised or endorsed by this author. The voyage from being swallowed to entering the stomach takes about 2 to 3 seconds.

At the bottom of the esophagus is the lower esophageal sphincter, which is a ring-like muscle that creates a barrier between the esophagus and the stomach. This sphincter relaxes when food enters the stomach, and tightens up again once the food has passed. Problems arise when this sphincter remains relaxed, allowing for the gastric juices of the stomach to rise into the esophagus, creating what you think would be called esophageal burn but, instead, somebody named it heartburn, overlooking the fact it has nothing to do with your heart. (I admit, however, that heartburn is much easier to say.)

Heartburn is often treated allopathically with antacids, which neutralize the acids in your stomach. Taking antacids may alleviate the pain for the time being but it also severely hampers digestion, creating even more problems down the line.

Stomach

The next step in our digestive system anatomy is the stomach. Once your food has made it to your stomach it may be there for up to a couple of hours. The stomach has three important digestive system functions. It stores consumed food and liquid, it mixes this with gastric juices to further break it down into a liquid and, lastly, it slowly empties the food (now called chyme) into the small intestine (which is by no means small by the way).

The stomach is lined with mucosa that helps to protect it from the intense acids it produces to break down food. This specialized mucosa does not allow for much absorption of nutrients although it does break down some water, some electrolytes, certain drugs (especially aspirin), and alcohol.

Much of the human digestive system is made up of mucosal tissue. When inflamed due to chronic inflammatory processes (Crohn’s disease, celiac disease or ulcers), or acute inflammation (diarrhea, heartburn), demulcent herbs such as marshmallow root and slippery elm can be used to soothe the irritated tissue.

How much time your food stays in the stomach depends a lot on the type of food that you ate. Carbohydrate digestion is really fast and carbs stay in the stomach for the least amount of time, followed by proteins, and then fats.

Knowing how fast your body metabolizes food is part of what can help you to determine which foods work best for you. For example, if your body has a fast metabolism, eating too many carbohydrates can leave you with frequent hunger and on a roller coaster of fluctuating energy. If, on the other hand, you have a slower metabolism, eating too much fat can leave you feeling too full and heavy long after you’ve eaten.

Small Intestine

Once your stomach has finished processing the chyme, it slowly enters the next major organ of the digestive system anatomy, the small intestine. The small intestine is where 90% of the digestive system functions take place. This hollow organ is an average of 22 feet long in an adult and is from 1.5 to 2 inches wide. The small intestine is covered in a mucosal lining along with small villi that all help to absorb the nutrients that will be assimilable by the body with the help of several digestive juices from the liver, pancreas, and the small intestine.

Bile

Bile is produced by your liver and stored in your gallbladder between meal times. When you start to eat, especially if there are bitter tastes in your food, the liver produces bile and the gallbladder squeezes out bile through ducts that enter into the small intestine. The bile has the specific action of breaking down fats.

Pancreatic enzymes

The pancreas produces a wide range of enzymes that further break down the carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in your food.

As your food changes into smaller and smaller molecules with the help of these various digestive juices it becomes ready for absorption through the small intestine.

Absorption

With the help of these digestive juices the chyme is broken down into smaller and smaller molecules and then finally absorbed into the circulatory system. Fat-soluble vitamins are stored in the liver and adipose of the body, while extra water-soluble vitamins are excreted through the urine. Water is also absorbed through the walls of the small intestine. Twenty two feet later it begins a slow entry into the large intestine.

Large Intestine

The large intestine is another important organ in our digestive system anatomy. It has several roles. It absorbs most of the remaining water as well as a few vitamins and electrolytes. It also holds the chyme until ready for evacuation.

A side note about toilet activities...

One interesting thing about the large intestine is the ascending colon. As the name suggests, the ascending colon literally travels up your right side before becoming the horizontal transverse colon, and then finally the sigmoid portion which travels down and ends at the anus.

In view of this anatomy, it makes sitting on a toilet to defecate a very unnatural phenomenon because it forces your body to work against gravity. Squatting while doing your duty on the toilet arranges your large intestine in a way that facilitates defecation. If you look around the world, squatting is much more common than our more modern, and supposedly superior, porcelain thrones.

Large intestine - Home to three pounds of bacteria!

The large intestine (and small intestine) is home to an amazing amount of bacteria that participate in further fermenting and breaking down your food. (Herbalist Chanchal Cabrera says that the bacteria in your colon could weigh as much as three pounds!). It is this fermentation that causes gas and flatulence. Gas can be an annoying nuisance or even extremely painful. Carminatives such as mints, fennel, chamomile, cardamom, and thyme are aromatic herbs that help to expel gas. Cooking with these herbs can help a problem before it starts. (This practice is inherent in some cultures, which is why you always find fennel candy as you walk out of the Indian restaurant after eating a meal; wonderfully spiced with carminatives.)

In a healthy person these bacteria are varied and abundant. Bacteria can become easily imbalanced with the use of antibiotics, diarrhea, poor food choices such as an abundance of sugar, and extreme colon cleansing programs. Traditional cultures around the world ate small amounts of fermented foods with every meal. This wisdom can be employed today to create and maintain a healthy balance in your colon. Some examples of fermented foods are kim chee, sauerkraut, miso, kefir, beet kvass and many more.

Appendix

When researching for this article on the digestive system anatomy I ran into several references that amazingly still referred to the appendix as useless. (I have a hard time believing that this incredible human body contains useless organs.) In fact, recent research suggests that the appendix plays a huge role in the immune system. Herbalist Jim McDonald says there’s research showing it may also repopulate the bowel with healthy bacteria after it has been purged.

The end of our journey into the human digestive anatomy

After the remaining nutrients and water are absorbed, the same peristalsis action that moved the food down your esophagus pipe now acts in the large intestine, moving it closer to the exit hole and creating the reflex to defecate. All that remains is some water, indigestible food, bacteria, products of bacterial decomposition, and inorganic salts.

Digestive System Disorders

Diarrhea happens when the food is moved through the system too quickly and water is not properly absorbed. This can happen because of irritants in the intestines. Astringents like blackberry and raspberry leaves can be taken to tone the tissue for better absorption, although for the most part it’s a good idea to initially let your body expel whatever it is trying to get rid of. The focus should be on staying hydrated and getting electrolytes.

Constipation, on the other hand, is when the fecal matter stays in the large intestine too long. Most commonly, this can happen from both hyper or hypo tonic tissue, lack of fiber in the diet, dehydration, lack of exercise, or excess mucous. Addressing these issues is much more effective in the long run than laxatives, herbal or otherwise.

David Winston recommends that optimal transit time, the time food enters your mouth to the time it leaves your body, is around 12 to 24 hours. To determine your transit time eat a nice serving of cooked beets and then record the time until you notice them on the other end. A nice bowl of borscht should do it.

What controls all these processes in the digestive system anatomy?

Although I have tried to mainly focus on the organs of the digestive system, it’s impossible to cut the human digestive system out of the body without at least acknowledging some other important roles. The nervous system, hormones, and the circulatory system administer different actions in harmony with the digestive system, leading to the stimulation of digestive juices, reflexes to keep things moving, and then carrying the digested nutrients to the various parts of the body.

Summary

Digestive system anatomy is a fascinating look into your body’s amazing abilities. I hope this gives you a better idea of how the digestive system anatomy works!

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.