Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

Methow Conservancy Interviews Rosalee de la Foret about her new book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods

and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine

Share this! |

|

Below is the transcript from the video above.

Sarah Brooks (00:00):

Hi, I'm Sarah Brooks, the associate director at the Methow Conservancy and I'm here today virtually through the wonder of zoom with Methow Valley author naturalist and herbalist, Rosalee de la Foret. Thank you Rosalee for offering to share your wealth of knowledge about plants and their healing potential with us. We're super sorry we couldn't pack the barn for your book launch party, but I know our e-news readers are going to be excited to hear from you and from what you learned writing your newest book, Wild Remedies.

Rosalee de la Foret (00:30):

Well, I'm just happy that we could adjust and pivot to these new times. Of course, I was looking forward to seeing everybody at the barn, I was looking forward to that and I'm also just really grateful that now as we're all hanging out at home, we can virtually share this as well, so thanks for being willing to adjust.

Sarah Brooks (00:52):

Well, my pleasure and it's super cool actually to see your beautiful library with all those nice plants in the background and people can forgive me for being in my artist husband's studio which is a little messier than we might have thought. But let's go ahead and dig right in; Wild Remedies is a cookbook, a botanical guide, and a natural history journal all in one, and I've had the good fortune to see a little sneak digital preview of it and it is an absolutely beautiful book to look at and I found the writing accessible and so engaging. The book begins with the story of Ellen Hutchins and I found her story remarkably poignant given our current moment in history. Would you tell us all a little bit about Ellen Hutchins and why you started the book with her story?

Rosalee de la Foret (01:43):

Yeah, I love that you loved her story because at this stage, so few people have actually seen the book. So that's some of the first feedback I'm getting. Ellen does have such a great story. So, Ellen Hutchins was the first female Irish botanist and I first learned about her story when I went to Ireland just under three years ago. I went to visit a friend, I arrived in the morning and my friend picked me up and we basically went to this Ellen Hutchins event. There's like a whole week long of activities in County Cork for Ellen. Ellen was born in 1785 and she had a rough start. Her dad died when she was two. She had lots of siblings, so there was a struggle. She went off to Dublin for school and she ended up getting really sick, like gravely ill and wasn't sure that she was going to make it.

A family friend ended up taking her under his wing, he was a doctor, and I just love that his prescription for her; maybe he gave her medicines, we don't know, but the story goes that his prescription for her was botany. He wrote that he thought it would stimulate her mind indoors while she's cataloging things, but also invigorate her outdoors. So under the prescription of botany, Ellen got better, and she also found that she just had an incredible gift, not only for cataloging plants, but also just seeing them in terms of that like scientific mind, but also just an incredible artist as well. So she specialized in seaweeds and lichens and her work is still treasured to this day. I mentioned there's Ellen Hutchins festival. She still has family. She was born in Valley lucky Ireland and she still has family there. Her artwork and botanical prints are still kept in museums all over the world and there are plants named after her. I loved that story of hers and I loved that the outdoors healed her basically.

Sarah Brooks (03:55):

Well, it made me think that maybe there's an Ellen Hutchins out there right now in the Methow Valley who's maybe feeling a little down or not feeling so great in this time of social distancing and isolation and maybe plants or just the natural world will be their door to something much, much bigger and happier. Well that all makes me want to know a little bit more about your own plants love story. How did you become interested in plants and all of their powers and what brought you to writing this book now?

Rosalee de la Foret (06:31):

Yeah, I didn't go into it slowly, really. I had a pretty big shift in my life. I was just out of college and I started going to a wilderness school and I was learning like how to make debris huts in the woods and just all sorts of survival skill type of stuff, and one of my teachers there was ethnobotanist and she just loved everything, plants and taught everything plants from like basket-making to foods and medicines, and it was very hands on course.

So, if we were in class it meant that we were outside and learning about everything around us. For me prior to that, I didn't know any plants. I think I knew what a cedar tree was maybe. During my first class ever with her, she kept talking about plantain, and I had just recently lived in the Dominican Republic where I ate plantain everyday, and I was like, "wow, plantain grows here?" I couldn't believe it. I just kept remarking on that and then she was like, "come on, I'll show you". We walked over to her driveway where there was the weed, plantago.

Sarah Brooks (7:45):

Not quite the same thing.

Rosalee de la Foret (7:46):

Yeah, it was not, so I really didn't know any plants whatsoever, so I started off just from the beginning there and it was such a magical thing for me to go from not knowing plants at all and just having, whether I was in a forest or even like an urban park or whatever, I didn't know the plants there. They were all like that miscellaneous green to me. So to be able to get to know them and not just like know their names. We would get to know their many names, but also get to know it through the seasons, like this is the first flowering plant of the season, so getting to know those cycles but also getting to know them as food and medicine and all the gifts that they have, and to interact with them also. It was just such an eye opening experience and it made my experience on this earth so much deeper. So that's a lot of what this book is, is kind of looking at the plants that grow around us.

I actually came to write this book, it is kind of a funny story, from that same trip to Ireland. I actually went to Ireland to visit a friend, but I also went to Ireland to see Tori Amos, who's a musician. My favorite musician, she's known for her cult following of fans, of which I am one, and it's pretty obsessive. At the time I had just published my first book, Alchemy of Herbs, and as soon as I published that book, people were like, "when are you going to publish your second book?", and I was like, "never ever, that was way too much work and I'm never going to do that again". But I had just published the book and it just seems so obvious to me that I should go to Ireland and meet up with Tori and give her a copy of my book, it seemed really normal. So, I went over there to do that and I got to speak with her for about five minutes and she was just so present and kind and gracious, and she's been my favorite musician since I was 12, so almost 30 years now; and she asked me a question while I was with her and she said, "what's the best way to take herbal medicine?".

She was probably asking, you know, like a tincture or a tea or whatever, and I have taught that for many hours myself as an herbal teacher. Maybe it was because of Ellen, you know, on my mind but I took it to that bigger place and mentioned, "it's the more we can incorporate plants into our lives and that they become really healing. So after that conversation, it's all I thought about for like three days. I just kept thinking about that, thinking about that, and then the thought just hit me as clear as day! "That's what your next book will be about and you need to start writing it now". And then seconds after that, I just realized, "and I'm going to write it with my friend Emily Han," who is my coauthor on the book. She's a naturalist, herbalist, and we've had so many conversations about all of these topics that it was just a natural thing. I wouldn't have written it without her and it was a really great partnership. So that's kinda how that book has come to be.

Sarah Brooks (8:55):

I hope Tori is working on a theme song for you.

Rosalee de la Foret (8:58):

I do too. Thank you. Me too!

Sarah Brooks (9:01):

We will definitely put the release of that up on e-news when that happens.

Rosalee de la Foret (9:06):

Great. I look forward to emailing you about that.

Sarah Brooks (9:12):

That leads me to another thing that I think is kind of where you were headed with your answer to Tori Amos, is that you describe Wild Remedies early on as an action guide. It's not just a book to read, it's something to do. What does that mean to you?

Rosalee de la Foret (9:31):

Well, there are a couple of layers of that. One is that I see my role as an herbal teacher is to inspire and empower people to use plants themselves. So, I've definitely failed if somebody just kind of memorizes what I say and just leaves it as words on piece of paper. I really want people to be able, if they are so inspired, to bring plants into their lives to make their own herbal medicines, to make their own wild foods, and really to experience the joy of nature for themselves.

So, it's an action guide in that we really want people to do this for themselves; and it's also an action guide because the book is not a bioregional book. We put a lot of thought into the plants that are in the book, and we chose plants that are widely available, but we didn't make it a bioregional book and we were very conscientious about that too. We wanted it to fit to people all over. With that, if we were super specific about certain climates, obviously it wouldn't work for a lot of people. So it's an action guide in that there are journal prompts and exercises to really help people to get to know their local ecology and their sense of place.

So, instead of us telling someone what is or what isn't true about their home and their area around them, we are kind of directing people or guiding people on how they can figure that out for themselves. So it can really be an action guide so people can do that for themselves and not just leave the words on the paper, so to speak.

Sarah Brooks (11:08):

Oh, I love that. Do you think you'd be willing to dig a little deeper with us on a couple of the plants that we might readily find here in the Methow.

Rosalee de la Foret (11:17):

Yeah, I'd love to.

Sarah Brooks (11:19):

I was caught first by the plant section and

the plant mallow, which I see frequently here in the Methow, and I

always just associate it with being awesome for butterflies, but I

learned it's awesome for a lot more than that. Maybe you could share a

little bit about mallow?

Rosalee de la Foret (11:39):

Yeah,

I'd love to. So yeah, Mallow. We are so lucky to have so much mallow

here. It loves to grow in gardens and other disturbed areas. I'll visit

the gardens of my friends and I have yet to find somebody, be really

excited; like, "look, Rosalee, I have all of this mallow growing in my

garden". I have yet to hear that, but I'm hoping to hear that one day. I

should mention that one of our local species, we have a couple, but the

one I'm most familiar with is Malva neglecta.

It's a

really common garden weed, but we are truly lucky to have it because it

has such specific and wonderful medicine. When you make a tea from the

roots especially, but the leaves and flowers somewhat as well, and you

make a cold infusion of the roots, then you get this substance that is

slimy and kind of gooey, and slippery; which is not normally how we

describe our medicine, especially with a smile, but it's such important

medicine because it's basically this mucilaginous or demulcent substance

that's really soothing and coating for dry mucus membranes. I don't

have to tell anybody watching this that we have a lot of dryness here in

the Methow, whether It's the summer or the winter.

Anytime

you're feeling like your throat is parched or maybe sometimes there's

like an irritation in the lungs or a dryness in the lungs; again, it can

happen anytime here, really, mallow is an amazing plant for that. I

drink it all throughout the summer. It's so hydrating, and again,

coating and so really great for irritation or just dryness, and it grows

so plentifully here. So, it's really wonderful for that.

I

don't know if you remember this, Sarah, but we've had some wildfires

here in the Valley and there's been a lot of smoke in the air, which is

also very drying and irritating to the lungs and can be quite a hazard.

Obviously, as we all know, we want to avoid that as much as possible,

but as we also know, we all live here, so we all experienced that and

mallow was one of the best plants for relieving that dryness and pain

associated with that.

That's why when I see it in people's

gardens and when I see it in my own garden, I'm just so excited. I'm

like, "yay, you're here" and I just know how helpful it can be. In our

gardens, it's also wonderful because has these deep tap roots that break

up soil and it brings up minerals from farther down in the earth, and

so if you let it just grow in your garden and let it go to seed and let

it die back down, you're really helping to remineralize your soils and

so it can improve soil health, so it's really lovely for that too.

Sarah Brooks (14:37):

Do you think that the gelatinous nature of it is where we get the term marshmallow? Is that accurate?

Rosalee de la Foret (14:44):

Great question, Sarah! Actually, the first marshmallows were made from mallow roots.

Sarah Brooks (14:52):

That might be more at home cooking that I could do.

Rosalee de la Foret (14:56):

I've

made and it's not that hard. But yeah., that's where we get that.

There's so many mallows out there. They're all used pretty similarly and

in other cultures around the world, they're widely eaten. So you can

eat the roots, you can eat the leaves. For the Malva neglecta, I love

the little ripe fruits, like those little seed pods. I call them little

cheese wheels. Do you know what I'm talking about? Like those little

buttons.

Sarah Brooks (15:25):

Yeah!

Rosalee de la Foret (15:25):

Those

are delicious. They can be a little time-consuming to harvest, but not

really. I'll harvest just a small handful and put them on salads and

they just have such a nice crunch. They're rich in those minerals, so

they have that added benefit as well. And then the flowers are lovely. I

mean you use the whole plant, there's not any part of the plant that

you can't use, and like you mentioned, the butterflies love them too,

and they are great for pollinators.

There's just, there's no

reason to hate this plant. That's what I'm telling you. I love it, love

it, love it. I will say that if people don't want to in their gardens,

that it's better to pull it earlier in the season and you can pull it

and dry it and you can make a tea out of the roots or the leaves, so you

can pull it, dry it, use it for later. Once it gets older, it gets a

lot harder to remove, and I think that's when people like start to

develop this negative relationship with it because it is much harder to

pull when it's older. When it's younger, it's pretty easy to pull up,

but why would you want to? Because you want a supply for, not only all

summer, but into the winter too.

Sarah Brooks (16:34):

Yeah.

Well, I want to talk a little bit about dandelions. As a conservation

organization, we get lots of questions about weeds and most of the time

people trying to eradicate weeds. So it's always awesome to hear that

something that you might be losing the battle against, as far as trying

to keep things native, might actually have some useful purposes. So,

tell me more about what I can do with the dandelion.

Rosalee de la Foret (17:04):

Yeah,

yeah. Do you have all day? Oh, dandelion... I love, love dandelion. For

the people who are watching, they might know if they follow the

newspaper, I tend to write a letter to the newspaper every year talking

about how much I love dandelions.

One day I was walking down the

street and I hear someone just yell out, "dandelion lover". I was like, I

should get that on a tee shirt. I love that. Yeah, so dandelions, I

definitely think that that's another plant that we are so lucky to have

here. It is a plant that we think was intentionally brought here from

Europe. It probably unintentionally came but it was also intentionally

brought because people could not imagine living without it, and it's

just such a sad thing to me that this idea of the so-called "perfect

lawn" has permeated our minds and the idea that this plant has become so

vilified. I know for me, anyway, when I kind of step out of that, it's a

really beautiful plant. Right now, my lawn is just starting to green up

and the first things that are green there are dandelion leaves and they

are so tender and delicious right now.

They are a lovely edible

green and you can just eat them. This time of year is perfect for them

because you can eat them and they have a slight bitter taste, which is

actually really beneficial to the digestive system. It kind of revs up

our digestive system. If you're like me and you've been eating potatoes

and beets and carrots and all of our winter storage vegetables all year

long, these are our first grains that we get, and they're just, again,

delicious. You can chop them up, add them to salads, you can stir fry

them, add them as greens like that. My favorite thing is a pesto. I love

making a pesto with the greens.

Sarah Brooks (18:55):

I think there's a recipe for that. Right?

Rosalee de la Foret (18:57):

There

is, yeah. Pretty much everywhere I go there's a recipe for that because

it really is one of my favorites. I bring that to potlucks a lot, and

it always causes a stir and people I love it. It's so delicious. So

those are the leaves, but you know, I was actually about to say that I

just don't understand all the hate against dandelion because it's so

beautiful. Where I live, I think I'm at like 2300 feet, so a little bit

off the Valley floor. It's about the third week of April, but you know,

definitely April is our month for dandelions when that first big bloom

comes out and those golden orbs, will just fill Methow, especially the

agricultural land and stuff. I just think that is one of the most

beautiful sites to just see as far as the eye can see, thousands of

those yellow flowers. They are some of our first flowering plants. The

bees love them, they're all over them, our honey bees, gathering the

pollen and nectar there. They're enjoying that, so that's another

benefit, and one of the side effects of dandelion flowers is joy and it

comes out in a couple of different ways.

One is just picking

them. I've picked countless dandelion flowers. I've done it with my

husband, I've done it with lots of friends. It just always is such a

joyful experience. I think it's very hard to not feel incredible heart

opening joy when you're picking dandelion flowers. They're really high

in lutein, which is wonderful for our eyes and all sorts of other

fabulous nutrients and you can put them in just about anything. You can

make a mead or a wine out of them. In the book, there's a recipe for

making a dandelion flower maple syrup cakes, so you can add them to

baked goods.

As you make your dandelion leaf salad, you can put

the flowers on top. You can make a junk food out of them and can fry

them up, like put them into batter and fry them up, fry up the flowers.

It's really yummy. You can just go on and on and on with dandelion, I

told you.

Rosalee de la Foret (19:04):

So, the secondary joy,

or maybe we're at the fifth joy of the dandelions, I've lost count, is

that if you let those flowers go to seed, then they give you free

wishes. This is such a generous plant. There's just so many lovely

things and those seeds are actually really important for the ecology as

well. Birds, like finches, like to eat them. They have a lot of

nutrients in them as well.

Sarah Brooks (19:32):

I will look at my dandelions differently.

Rosalee de la Foret (19:36):

The

roots are lovely too. I can't not mention the roots. They can be

harvested. They have a little of a bitterness to them. Really high in

nutrients. Kind of like the mallow, they're going deep into the earth

and pulling up those nutrients. You can eat those in a stir fry, you can

pickle them, you can extract them with vinegar because they have all

those nutrients and minerals in them. Then you have a mineral rich

vinegar that you can use to make your salad dressings. Probably my

favorite thing though to do with the roots is to toast them or roast

them up, then you simmer them in water and it gives this rich roast.

People call it coffee-like, but there is no caffeine and it doesn't

really tastes like coffee, but it's like this rich roasted taste that's

just so yummy and that's probably one of my most drank teas. It's so

delicious.

Sarah Brooks (22:27):

Fascinating.

Rosalee de la Foret (22:28):

Yeah.

The dandelions, they just keep giving and giving. They're some of our

very, very best plants. And then of course, when we choose to poison

these plants, then we're not only harming them, but there's so many

repercussions for the whole ecology. For us, for all of the creatures,

like the bees that are feasting on them, the birds and just everything

seeping into our groundwater. So, there's really no reason to poison

them and every reason to love them.

Sarah Brooks (22:59):

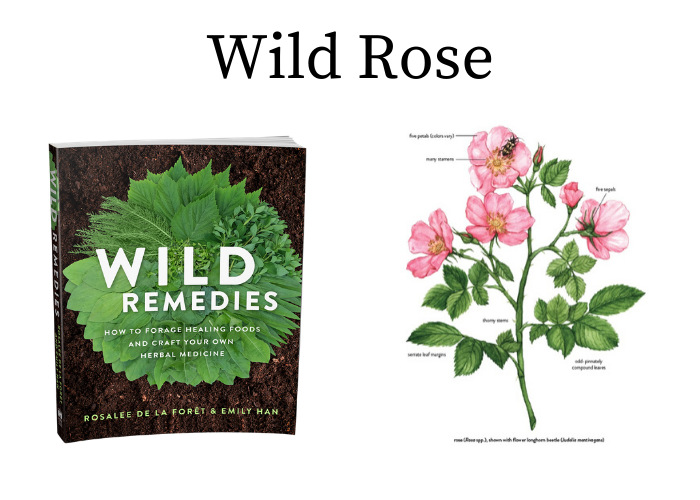

And what about the wild rose, another one of the more favorites in the valley?

Rosalee de la Foret (23:05):

Yeah.

I don't think I'm going to have to try so hard to get people to fall in

love with wild rose. You see, I was really working it with mallow and

dandelion. Even the way you said it, you were just like "yeah, wild

rose". Yeah, no surprise. One of my very favorites and one that it's

easy just to have a really special relationship with here in the Methow

Valley because we are just so blessed to have so many wild roses. Wild

roses are such a different thing from our domesticated roses because

they're just so vibrant, and the smell from them is just so utterly

fantastic.

So people often ask me if they can use domesticated

roses instead of wild roses, and I'm like, "yeah, but why would you want

to?". Of course, that's kind of like a place of being blessed here in

the valley where we have access to so many wild roses. But yeah, that

smell is just so incredible and certainly medicine within itself and

with wild Rose here in Methow Valley, it gives us an opportunity kind of

to step beyond our gardens and look a deeper ecological connections

because there are so many with the roses. We can think about where they

like to grow and how they like to have their feet wet and be near water

source. We can think about the soils that support them.

They

definitely do best when they have a little bit more sunshine, although

we can find them in the forest as well. And then there's just so many

creatures. One of my favorite things about wild roses is when you walk

up to them when they're in bloom, in the May-June-ish area, then you

walk up to those and you can hear them before you get there.

Sarah Brooks (24:48):

Yes, they are alive!

Rosalee de la Foret (24:48):

Like

all the pollinators, yeah, all those buzzing of the bees and

everything, so I love that. And when they grow in briers, they're

protecting a lot of creatures, providing habitat for them. Then, of

course, the birds in the fall, loving those Rose hips.

So there's so

many different ecological connections there and it's never boring. You

can spend a lot of time out there enjoying getting to know the roses and

all of the beings that are interdependent and related with each other

through that. So rose's offer us fantastic medicine on so many levels.

Just spending time with our wild roses is medicine within itself.

When

I think of Rose, I really think of medicine for the heart and Rose

works on a couple of different levels. In our culture, if you love

someone, you tend to give them roses. Right? That's a thing.

So

roses are known to be the show of love, and they also have a lot of

benefits for the physical heart as well. Rose hips, really wonderful for

modulating inflammation and eating those can really help. Heart disease

often has this undercurrent of inflammatory disease and rose hips are a

wonderful way to bring an antioxidant rich inflammatory modulating

thing into your life, and they're so delicious so they're easy to bring

in. I don't think there's ever been a spring or early summer here in the

Methow where I haven't harvested rose petals.

Right now I'll

just say they're my favorite thing to harvest. They're not like

harvesting burdock where you're like sweating and working hard and

getting through the sandy soils. They are easier, you're just like kind

of plucking them from the bush, smelling the smell, cohabitating with

all those pollinators. What I like to do, my most favorite thing to do

with them is to make an infused honey. I carefully harvest the petals.

There

will be, you know, the crab spiders, golden rod spiders, they love to

be in there as a lot of other pollinators, so I am always careful to not

disrupt them. You can harvest just the petals, leaving the rest of the

fruit behind to develop into the rose hips.

So I harvest those,

shake out the flowers, let the buttons go, and then just lightly fill a

jar, so a glass jar, like a glass canning jar with the flowers and then

pour honey on top of that, stir it up, pour a little bit more honey on

that. This is like the Ambrosia of the gods, right? That smell and taste

just extracts so well into that honey and this makes great gifts and if

anybody has extra, you're welcome to gift it to me. I give it as gifts.

I mean it's just such a pure gift. You're getting honey from one of our

local beekeepers, getting the petals from our local wild roses and it

is truly a gift of the Methow. It's wonderful anytime of year, but I

especially love it in the winter. Put it on crepes, put it on biscuits,

use it in tea, on and on. There were so many ways to enjoy it. That's

just like medicine within itself, just the joy of getting to taste a

piece of June in December. Yeah, that's one of my very favorite things.

And

the Rose hips, as I mentioned, they're used as medicine as well. They

are also nice infused in honey, but you need to de-seed them first,

which is a little bit more work. When I lived on the West side, there's

the big rugosa roses there and they're big like big fleshy, they're almost like plums. So those are really easy to de-seed.

Sarah Brooks (28:46):

Yeah, ours not so much.

Rosalee de la Foret (28:46):

The

ones we have here, they are kind of thin, but it can still be done. I

like to dry them whole and use them in teas. They're famous for being

really high in vitamin C, but vitamin C is a very delicate to vitamin

and so it degrades really quickly. So the best way to enjoy vitamin C

from the Rose hips is to eat them fresh off the bush. I love that. In

the fall, you're going of on all your fall hikes and you can nibble some

off of this bush and some off of this bush, and you'll see they have a

wide variety of tastes. They are not all, even from the same species,

they have diverse tastes. Some will be bland, some will be bitter and

some will be sweet. And so it's always a surprise to see which is which.

Sarah Brooks (29:33):

I love that.

Sarah Brooks (29:36):

Well,

it's been such a fascinating conversation and it's just a tip of the

iceberg on all the different plants that you go into. So thank you

again. I'm hoping as we sort of get to the end of this interview, we can

go back to the beginning of your book. Chapter two of Wild Remedies is

called "getting to know where you live". I feel like we're all getting

to know where we live on a whole different level during this era of

staying home and social distancing. Can you maybe share with us just a

few of your tips on how to really get to know where you live or maybe

see it in a different way if you feel like you've been looking at it for

a long time and why you think it matters?

Rosalee de la Foret (30:18):

Yeah,

absolutely. Well, the first step is go outside every day, which I know

we're really good about that here in the Methow. We are so blessed to

have beauty just right outside our doors. But I couldn't stress that

enough, you know, just getting out to see what's there and getting out

of our brains and our thinking minds to be in a place of awareness and

observation.

There's just so much going on out there, and so to

get outside and then approach it all with wonder and curiosity. I love

to just think about things like, "I wonder why". Like, just seeing

something, "I wonder why the ceanothus bush curls up its leaves

in the winter time". Or I wonder why I hear this bird more often right

now, or I wonder why that plant is growing in this particular area. Just

to bring that curiosity is really fun and it's fun to figure things out

for yourself. Just by wondering that and thinking about that it's like,

"Oh, I wonder why the roses grow there". "Oh, I see that there's

actually a little spring running through there and it must like the

water there", or whatever the case may be. But then of course, we live

in such an amazing place to learn from other people too. So many

opportunities to do that, like whether it's a course through the Methow

Conservancy.

I love the winter courses that's always offered.

Going to first Tuesdays, going to the Methow Valley Interpretive Center,

going on nature walks and there's countless opportunities to go there

and to bring your curiosity and wonder and ask about this place. I have

noticed this, you know, what's going on, and I think so many of us do

that anyway.

You know, the Methow has a French club. It's Monday

nights and we're meeting by zoom these days. So taking it virtual and

yesterday the conversation, you know, it was like people sharing like

what birds they're seeing and asking questions and wondering, you know,

"why does it do this?" So I think we're already so good at that, but

it's like this never ending spiral of wonder and joy of figuring things

out.

Sarah Brooks (32:28):

I love the idea of reminding us as

adults to keep that wondering, questioning alive. Any of us who are

currently sequestered with any children are probably being asked lots of

questions. There's lots of wineries going on, but we do a school yard

science program with fourth graders and the session we did, right before

the stay at home order was an outdoor nature journaling and piece of

paper and break it into four quadrants. In one corner you wrote about

it, "I notice", in the other you wrote, "it reminds me of", and then the

third was "I wonder", and then the fourth was to do it a drawing or a

sketch and to realize you see things differently when you draw them.

It

was so fascinating to me. Certainly different students had different

quadrants they liked to spend more time in, but the, "I wonder", was

always just jam packed full like that. The paper could not have enough

space in it. I love that because they had a million questions. "I wonder

if that eats pizza", and it's just all over map, right? But such a

wonderful place to get lost in and maybe as we have some time to spend

outside, we can just let ourselves get lost in wondering.

Rosalee de la Foret (33:46):

Yeah,

yeah, I love that. And I was actually going to bring up journaling too.

I love keeping a journal of firsts, so I know it's like kind of a

common naturalist practice; but for example, I've been following when

the Phoebe's get here for the past 12 years. So I have that information.

When I first hear the Phoebe's arrive, it's so amazing. They always

show up around the same days.

Sarah Brooks (34:07):

Yeah,

they're like clockwork. We watch when the tanagers come to our office in

downtown Winthop and it's uncannily within like three or four days,

whether it's been a long winter or a warm spring or, whatever.

Rosalee de la Foret (34:25):

I

wonder what their lives are like. Yeah. So keeping that journal and I'm

admittedly the best about it in the spring when it's like easy to

notice those things and I'm like starved for it anyway, so there's that,

it's easier, but being able to see those and kind of count on those,

you know, like the Phoebe's are my friends. I'm counting on them every

year to show up, and I'm wondering about them and just that relationship

that forms from that.

In terms of why it matters, I think, you

know, it feels kind of funny to answer that question for the Methow

audience because I know that I'm speaking to the choir here, but I did

think about it and in terms of just my own journey, I really got a

message when I was growing up that if I loved nature, I would leave it

alone because we have so many horrible examples of humans messing up

nature, and that was definitely the thing I was told, you know, stay on

the trails, don't touch, keep off, use your eyes, use your ears, but

that's it. And I can certainly understand that fear, but I think it's

imperative that we learn to see ourselves as a part of nature and not

apart from nature.

And the best way to do that is by interacting

with nature and by becoming grounded and rooted in place. Some of us, I

know were born here, many of us weren't, and we're getting to know this

landscape, getting to know the rhythms, whether we've been here one

year or whether we've been here 50. I think that is such important work.

I know it's important for my heart because it brings me such a

joy, but it's also important to form those relationships of reciprocity,

of tending to the land. If we use only our eyes and our ears, it's just

a fragile relationship. The more we interact with plants on a deeper

level and the world around us, the just the deeper those relationships

form and the more that reciprocity forms and that deeper, stronger

relationship means that our ties to this land become that much stronger,

as we see our ties to the land really, really matter.

When a

company shows up and they want to mine for copper in our headwaters, we

show up when we say no, and we do that in very strong ways because we

have that connection to the land. We know our mountains, we know our

rivers and we are here to protect them. I think that comes from us being

out there and having that relationship on so many different levels. I

think that nature connection and again, seeing ourselves as a part of

nature and understanding our role within it, you know, to protect it

and, um, and to be a part of it and experience, to me, that's the joie

de vivre.

The reason we're here to experience life on this

earth. And so again, when I walk out to the forest and I'm able to look

at the Doug fir and the pine trees and tell them thank you for helping

me with my congested cough, that means a lot to me. To be able to see

all the elder shrubs and thank them for helping keep me protected

against viral infections. That means a lot to me. To look out and see

the mullein leaves, one of my favorite plants. Those mulleins, you know,

they restore land that have been disturbed. They're like a bandaid for

the earth and helping to restore soils. And also I mentioned mallow

being so great for wildfire season.

Mullein, I would not want to

live a wildfire season without mullein. So to be able to walk out on

the landscape and saying, "hi friends, thank you", and then not just

show up like wanting something, but show up being able to offer

something as well in terms of tending them in a way that means that we

have an abundant supply and harvest for many generations to come and

that we can actively work to create a more resilient landscape. Those

are all things that we need in this beautiful Methow Valley.

Sarah Brooks (38:27):

That's

a beautiful way to end this. Thank you so much for being flexible and

nimble with us as we transitioned from in-person first Tuesdays to

virtual zoom first Tuesdays. You have been wonderful and we hope our

e-news readers enjoyed this. Your book comes out, I believe, April 7th?

Rosalee de la Foret (38:50):

Yeah, April 7th.

Sarah Brooks (38:50):

And

then I believe that Glover Street Market will have it and Trails In

bookstore. If you want to preorder a copy, you can order it right now at

Trails In bookstore through their online web service, which will have a

link to e-news and they will either mail it to you or have it available

for curbside pickup. So thank you and congratulations so much. It's a

beautiful book and a really neat way to look at our own backyard a

little differently.

Rosalee de la Foret (39:18):

Well, thanks

Sarah. Thanks so much for being here, for your great questions and to

the Conservancy for hosting this. I really appreciate it.

Sarah Brooks (39:24):

You bet. Thanks everyone.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.